Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr. surveyed the racing grounds in front of him with admiration. It was 1872, and the Grand Prix de Paris was in full swing at the Hippodrome de Longchamp, Paris’s newest racetrack. Near the starting gate were gathered some of the finest horses in all of France, the sleek animals appearing to have been carved from pure muscle. Along the course stood well-attired gentlemen and their wives, the ladies carefully coifed, dressed in colorful silks and chatting with friends beneath their parasols. Many of the spectators had arrived via steamship or private yacht by way of the River Seine.

The Grand Prix’s races were certain to be exciting, but this collection of French elites was very nearly as eye-catching to Clark. The entire spectacle put him in mind of Epsom Downs, a track on the outskirts of London. Just weeks prior, Clark had attended Epsom’s Derby Stakes, which had been run since 1780, and he found it a similarly prestigious race, just as impressive in its horsemanship and just as stylish.

There was no ignoring the pull. The one-two punch of these two European horse races cemented in Clark’s mind an idea that had been building there: The United States needed an elite new race of its own. And there was no city better suited to host it than Louisville, Kentucky.

Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr. was the grandson of explorer William Clark — of Lewis and Clark Expedition fame — and was named after his grandfather’s famous cohort. The younger Clark was also the great nephew of Louisville founder George Rogers Clark. And while Meriwether had no real background in horseracing, he banked on his family’s social status, financial means, and close ties to the horse-breeding industry.

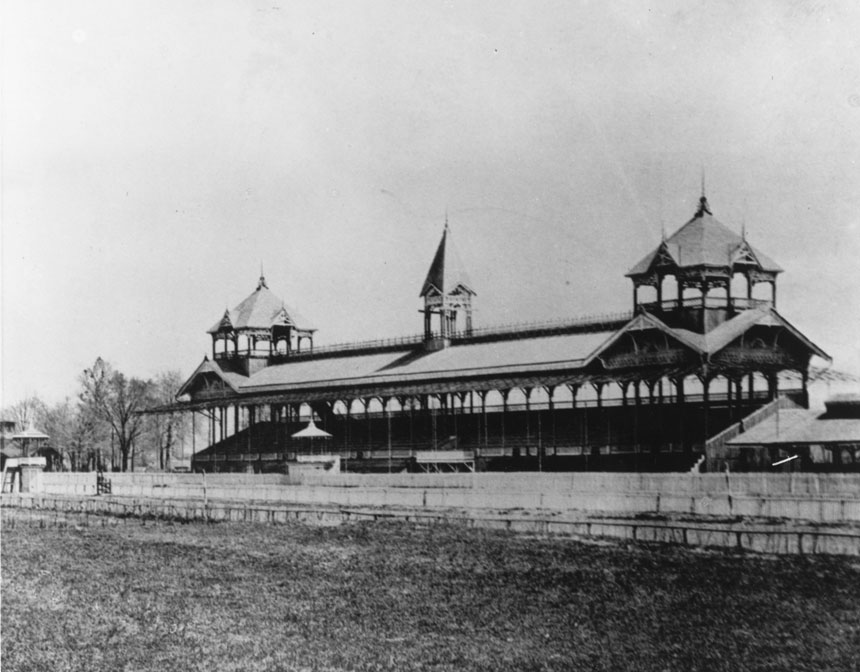

Following his return from Europe, Clark approached his Louisville uncles, John and Henry Churchill, to negotiate a lease on a portion of their land for a new equestrian club and racetrack, the Louisville Jockey Club and Driving Park Association. The 80-acre course would come to be called Churchill Downs in 1883.

“By the end of the Civil War in 1865, horse racing in America had been devastated,” says Chris Goodlett, senior director of curatorial and educational affairs at the Kentucky Derby Museum. “Most of the nation’s horses had served the war effort or been used as means of transportation. Nationwide, there would have been little interest in something like horse racing during the war years, and few horses to race.”

Clark’s family and business associates in Louisville would have been eager for a new outlet in which to showcase their breeding stock and a new means of growing their herds. Furthermore, in the aftermath of a physically and commercially devastating war, Kentuckians were only too happy to embrace the pleasant diversions of a new horse race.

“There certainly would have been a yearning for normalcy,” says Goodlett.

And so, on May 17, 1875, the Louisville Jockey Club staged the first running of the Kentucky Derby. Fifteen three-year-old Thoroughbreds gathered on the course’s dirt track, lining up before a crowd of 10,000 onlookers to run a 1.5-mile course (the race distance was reduced to 1.25 miles in 1896). Once the track judge verified that the horses and jockeys were in good form and in their proper positions, a drum tapped, a flag fell, and the race was off.

The winner, a colt named Aristides, streaked across the finish line in 2:37.75, ushering in the “most exciting two minutes in sports.” Oliver Lewis, an African-American jockey, rode him to victory.

Louisvillians quickly took to their city’s new racetrack, attending the Kentucky Derby and other races at Churchill Downs in ever-increasing numbers. In 1894, the growing crowd size necessitated construction of a new 285-foot grandstand, and in 1895, a pair of elegant, iconic twin spires were placed atop the building.

While elite attendees watched the action from the stands, ordinary folk gathered to watch the event from the infield, where attendance was free. There, crowds of all races and classes gathered in horse-drawn carriages and on picnic blankets, dining on sandwiches and drinks provided by roving food vendors. The Kentucky Derby had become Louisville’s biggest party.

But despite its local popularity, the Kentucky Derby struggled financially, and in 1902 master promoter Matt Winn took over as vice president and general manager of Churchill Downs. Determined to transform the Derby from a beloved Kentucky horse race into America’s can’t-miss pastime, Winn launched a marketing program that included many of the iconic Derby traditions still enjoyed today.

The promoter introduced the red rose garland that would adorn the Derby winner and designed a winner’s circle where the prize would be presented with fanfare. “Mr. Derby,” as Winn soon came to be called, negotiated a partnership with the Preakness and Belmont Stakes that would come to make up the Triple Crown. He established the tradition of singing “My Old Kentucky Home” on race day, oversaw the naming of the mint julep as the official drink of the Kentucky Derby (as well as touting the collectible souvenir glasses in which the drinks were sold), and in the 1940s, converted the racetrack’s infield into a victory garden to advertise the Derby’s support of the war effort. Winn also made a habit of inviting the nation’s top celebrities to the Kentucky Derby each year, which gave a significant boost to viewership once the race appeared live on television.

“It’s impossible to see the Kentucky Derby as the success that it has become without the involvement of Mr. Derby,” says Goodlett.

While he was in Europe, Meriwether Lewis Clark was inspired by the Epsom Derby and the Grand Prix de Paris. But he was no less impressed by the Epsom Oaks, a counterpart to the English derby reserved for three-year-old fillies. Even as Clark was organizing the Kentucky Derby, he began developing plans for a companion race to accommodate owners’ different approaches to the training and racing of female horses. While the Kentucky Derby has always been open to horses of both genders — two fillies raced in the premiere 1875 event — only three fillies have ever won, most recently Winning Colors in 1988.

On May 19, 1875, two days after the running of the first Kentucky Derby, the Kentucky Oaks launched its inaugural race for fillies, with Vinaigrette taking home the prize. The Kentucky Oaks continues at Churchill Downs today, making 2024 the sesquicentennial year for both races.

“The Oaks used to be known as ‘Louisville’s Day at the Derby,’ more of a local affair,” says Jessica Whitehead, curator of collections at the Kentucky Derby Museum. But attendance at the Oaks in recent years has grown significantly, she added, drawing about 100,000 spectators in 2023 as compared to the Derby’s 150,000. It’s a fair assumption that as the Derby’s popularity and ticket prices rise, and as race promotion and purse size at the Oaks increase, fans from all geographic areas will consider the Oaks as an alternative.

“These days the Oaks feels almost the same as the Derby — just more pink!” says Whitehead.

Like the winners of the Kentucky Derby, Oaks victors are festooned with flowers, namely pink “lilies for the fillies.” And like the Derby, the Oaks has an official drink, the Oaks Lily, a pink cocktail made with cranberry juice. Further emphasizing its female focus, the Kentucky Oaks urges spectators to dress to impress, preferably in pink attire and crowned with pink fascinators. The race also sponsors fundraisers related to breast and ovarian cancer.

If the Kentucky Oaks has a reputation for being hyper-attentive to fashion, both the Oaks and the Derby have encouraged fancy dress from the start.

“Meriwether Lewis Clark wanted to make a spectacle of his new derby from the very beginning,” says Whitehead. “On Clark’s visits to Europe and Saratoga in New York,” the latter of which opened to the public about a decade before Churchill Downs, “he encountered the view that Kentuckians were merely backwoods country cousins. Clark’s new race in Louisville was meant to prove them wrong.”

Clark began with basic concerns: piping running water out to the south side of Louisville. It was no mean feat in 1874, considering that Clark’s new track lay three miles from downtown Louisville.

As for fashion, the Derby’s 19th-century upper-class attendees had no difficulty satisfying Clark’s hopes for a stylish affair. The elite were accustomed to showing off their wealth and status at social events, appearing at the Derby dressed in fine wool suits, silk skirts, and feather-studded hats.

Decades later, just as American women began ditching formal skirts and hats in ordinary life, increasing numbers of celebrities began appearing at Churchill Downs, many of them vying for camera time with flashy clothing and inspiring their fellow attendees to do likewise. Elaborate race-day hats might have waned again in the early 2000s were it not for the televised marriage of Kate Middleton and Prince William, an occasion that brought flamboyant headwear back into the American consciousness.

“There has always been a desire among race attendees to rely on fashion as a way to stand out,” says Whitehead. “We think of it as the ‘Racetrack as Runway,’ or the ‘Derby Fashion Parade.’”

Extravagant clothing is only one aspect of the carnival atmosphere in Louisville each spring. The idea of a weeklong Derby Festival was first proposed in the mid-1930s, under the leadership of Matt Winn. Organizers planned a parade with floats, marching bands, and “prancing horses, a sort of history of the horse race put to music and flowers,” according to a February 1956 story in the Louisville Courier-Journal.

A monumental flood quashed plans for the citywide party of the ’30s, but the idea was successfully reprised in 1956. The inaugural Derby Festival was meant to extend the holiday vibe to a full week of family-oriented events, particularly for locals who couldn’t afford a ticket to the races.

The first Derby Festival comprised a single event, the Pegasus Parade, named for the winged horse of Greek mythology. The city staged a free procession of the colorful floats, marching bands, and equestrian teams that early organizers had anticipated. Some 50,000 Louisvillians are estimated to have attended.

Over the course of six decades, the Derby Festival has grown to include 70 events over the month leading up to the big races, ranging from a marathon and fashion shows to concerts and steamboat races on the Ohio River. Particularly popular is the hot air BalloonFest and Thunder over Louisville, the nation’s largest annual fireworks show. The Pegasus Parade, now approaching its 68th year, lasts two hours and stretches 17 blocks through the heart of downtown Louisville.

The Kentucky Derby has succeeded in becoming the longest continually held sporting event in the U.S., taking place even during two World Wars and the COVID-19 pandemic, the latter before an empty stadium. As many as 20 horses will vie for a $3 million purse at the 2024 running of the Kentucky Derby on May 4.

It’s easy to get lost in the statistics of the Kentucky Derby, but Jessica Whitehead believes we’re missing the point if we focus too heavily on numbers. “The Kentucky Derby is special because of the human stories and the American history that it represents,” she says. “The Derby is an exercise in nostalgia, in good ways and in bad.”

When the 150th Kentucky Derby takes place this year, when the starting gates fly open and the young Thoroughbreds and their jockeys run for the roses, the atmosphere at Churchill Downs will be more electric than Meriwether Lewis Clark could ever have dreamed.

Amy S. Eckert is a freelance travel writer and photographer whose work has appeared in numerous publications, including National Geographic Traveler, AARP, AFARM, and the Chicago Tribune. For more, visit amyeckert.com.

This article is featured in the May/June 2024 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access.

Subscribe now