‘They gave us freedom’ – D-day veterans celebrated in Normandy

By Katya Adler, BBC Europe editor

Marianne Baisnee

Marianne BaisneeIt’s impossible not to be swept away by the warmth and energy in the stone-clad villages up and down the Normandy coastline this 80th anniversary of D-Day.

British, US and Canadian flags flutter from garden gates and lampposts as far as the eye can see. Music from the 1940s drifts through village squares, while country lanes roar with column-upon-column of World War Two-era military jeeps.

Driving them are laughing, waving men and women from all over Europe. Germans, Dutch, Belgians and Brits from all walks of life, who this week have chosen to don Second World War Allied military uniforms, to honour the 150,000 soldiers who landed here in Nazi-occupied France on 6 June 1944 – changing the course of 20th-Century Europe as they did so.

How different things look now. After decades of Europeans pledging “never again”, war is back on this continent on a scale not seen since World War Two, with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Eighty years ago, Germany was the enemy. Russia, a key ally. Its pyrrhic victory on the eastern front was fundamental, like the western front Allied assault that followed D-Day, in bringing Nazi Germany to its knees.

Yet this Thursday, at the official international D-Day ceremony, Germany’s Chancellor Olaf Scholz will stand shoulder-to-shoulder with France’s President Emmanuel Macron, US President Joe Biden and the heir to the British throne, Prince William.

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky has been invited too. Russia’s Vladimir Putin most pointedly has not.

President Macron’s office insists the World War Two sacrifice of the Soviet people and their contribution to victory will be honoured this year as always. But it says “it will be remembered that the Eastern front was not just Russia, but also the Ukrainians, the Belarusians and all the other countries that were part of the USSR.”

The pain and humiliation of occupation, the deprivation of freedom facing or threatening millions in Ukraine, is something the Normands understand all too well. They make sure younger generations appreciate what Allied soldiers risked – and lost – to liberate them.

‘They gave us our freedom’

Marianne Baisnee

Marianne BaisneeThe star attraction in Normandy this week is certainly not world leaders. It’s the surviving D-Day veterans, the youngest of whom are now in their 90s. Wherever they travel along the coast, they’re feted, photographed and fawned over, especially by the locals.

I met young mum Vanessa Foulon, queuing with her six-year-old son to get a D-Day commemorative cap signed by an American veteran. Why is this so important to them, I asked?

“Liberté” she said simply. “They gave us our freedom.” And she burst into tears.

“People here are nice,” 99-year-old US veteran Donald Cobb told me. “We enjoy coming back.”

He’d been taking part in a veterans’ march in picturesque Sainte-Marie-du-Mont. The streets here are festooned with banners claiming to be “the first liberated village”.

Donald remembers landing on nearby Omaha beach at 05:30 on 6 June 1944. The water was choppy, the wind biting, he says.

Marianne Baisnee

Marianne BaisneeAt 19, he must have been petrified.

“Honestly,” he said, “I would rather have been anywhere else.”

Yet his modesty was humbling.

“We did what we had to do,” he told me. “I don’t feel like a hero, I’m glad we were able to help. I feel good about that.”

France feels conflicted about its own wartime history. The country was split after it signed an armistice agreement with Nazi Germany in 1940. The Germans occupied northern France and all along the Atlantic coast, to the Spanish border. The south was managed by France’s Vichy government, which collaborated with the Nazis.

Yet D-Day events marking the contribution of French men and women who worked for the French Resistance seem somewhat muted, compared to the boisterous array of events commemorating Allied soldiers.

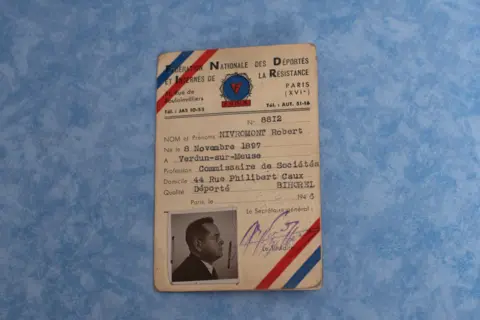

“I don’t forget them. Please don’t forget them,” urged Catherine Nivromont, looking at me intently with her clear blue eyes.

Catherine’s brother, Pierre, was just 17 in 1944. He worked with other Resistance members, gathering intelligence on German positions along the Normandy coast, to help Allied forces plan their June assault.

Marianne Baisnee

Marianne BaisneePierre was in touch with locals who did German soldiers’ laundry. Their clothing was marked with battalion details, revealing the quantity and location of troops.

“Each person played their small part,” Catherine said. “Under occupation, you had to resist silently, secretly. You never knew who you could trust.”

Both her brother, Pierre, and her father – who was also in the Resistance – were eventually betrayed by a Frenchman they had relied on to help make fake passports for Allied airmen stuck behind enemy lines.

Both men were sent to Nazi concentration camps, initially to Auschwitz, and were separated afterwards.

“I think his homeland was more important to him than family,” Catherine observed a little sadly. “The risks he took were huge.”

Catherine Nivromont

Catherine NivromontBut you’re proud of him, I asked?

“Oh, yes. So proud. That is why I see it as my job to still visit schools and universities. To tell the youth what the Resistance did, and how much they sacrificed for us.”

It’s thought only 2% of French citizens worked full time for the Resistance, though they relied on a far broader network of people willing to help.

For such a small group, they’ve had a big influence on modern-day France too.

Many in the Resistance were left-leaning. A large proportion, communist. After the war, they helped set up the new French Republic, implementing France’s strong welfare and health system which is still firmly in place today.

Marianne Baisnee

Marianne BaisneeBack on Omaha beach, I found a group of European youngsters, energetically rehearsing a presentation of D-Day testimonies – including a French child, an Allied soldier, a frightened young German conscript and a resistance fighter – as part of Thursday’s international ceremony.

Why had they volunteered for the project? As a German-Austrian national, Helena told me she felt it important to send a message of peace.

“Freedom for all!” was the heartfelt priority for Kate from Ukraine.

But 80 years on from D-Day, storm clouds hang heavy over Europe. If President Putin is victorious in Ukraine, nearby nations like Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania fear they could be next.

Since World War Two, Europe has relied on the US to have its back in terms of security. But elections in Washington are fast approaching. If Donald Trump returns to the White House, he’s made clear to Europe’s leaders they should take nothing for granted.

Additional reporting from Kathy Long and Marianne Baisnee

Related

A New Book Argues That What Happens in Europe Doesn’t…

Remaking the World: European Distinctiveness and the Transformation of Politics, Culture, and the Economy by Jerrold Seigel “No issue in world

Poland plans military training for every adult male amid growing…

Poland’s prime minister, Donald Tusk, has said his government is working on a plan to prepare large-scale military training for every adult male in response t

2025 European Athletics Indoor Championships: Ditaji Kambundji secures women’s 60m…

Switzerland’s Ditaji Kambundji walked away from the 2025 European Athletics Indoor Championships in Apeldoorn on 7 March with much more than her first Europea

Takeaways from the EU’s landmark security summit after Trump said…

BRUSSELS (AP) — European Union leaders are trumpeting their endorsement of a plan to free up hundreds of billions of