Europe braces for ‘most extreme’ military scenario as Trump-Putin 2.0 begins

LONDON — All over Europe, there are signs of a continent steeling itself for the unthinkable.

Lithuania plans to lay mines on its bridges to Russia, ready to detonate should Kremlin tanks try to cross. In the nearby Baltic Sea, NATO ships are hunting Russia’s so-called “Shadow Fleet” accused of cutting undersea communications cables. And in Europe’s skies there are plans to construct a vast missile defense system, similar to Israel’s “Iron Dome” but with the explicit purpose of shooting down rockets launched by Moscow.

European governments and citizens worry that an emboldened Kremlin may turn his armies their way after Ukraine. There is also widespread nervousness that the new president — an isolationist — has suggested he may not defend America’s historical NATO allies if they are attacked by Russia.

While President Donald Trump this week criticized Vladimir Putin, Trump has showed few signs of a meaningful shifting from that position. On Thursday, he said in an interview with Fox News that “Zelenskyy was fighting a much bigger entity,” and that “he shouldn’t have done that, because we could have made a deal.”

He said little new about NATO or Europe, only reiterating his latest demand for European allies to pay 5% of their GDP toward defense — more than twice the NATO recommendation — and lamenting how much more Washington has spent than Brussels supporting Ukraine’s defense.

“NATO has to pay more,” Trump said. “It’s ridiculous because it affects them a lot more. We have an ocean in between.”

The stakes couldn’t be higher. European officials have repeatedly stated that Putin is preparing for a war with the West. For many this is already happening, with think tank analysts, governments and NATO itself accusing Moscow of “hybrid warfare” attacks — from election interference to trying to crash airliners with firebombs.

“The Europeans are taking this very seriously,” said retired Lt. Gen. Ben Hodges, the former commander of the U.S. Army in Europe between 2014 and late 2017.

In particular, countries in Eastern Europe nearer the Russian border “know that this is for real, because they live there,” Hodges added. “It’s only those people who live in Western Europe or the U.S., far away from the Bear, who say: ‘Come on, this is not going to happen.’”

The core tenet of NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, is that allies will defend any fellow member under attack. The only time this “Article 5” promise has been triggered was after 9/11, when Europe helped the United States patrol its skies in an act of solidarity. The main message of that stipulation is that if a country attacks Europe, it will also be at war with Washington, and its intended audience is Russia.

But Trump has repeatedly suggested he would ignore Europe’s distress call.

Plenty of those in Europe’s corridors of power agree that a complacent continent has for too long relied on Washington’s protection. French President Emmanuel Macron, a longtime proponent of European self-reliance, said Monday that Trump’s second term should serve as a “wake-up call” for the continent.

In comments made at a defense conference on Wednesday, the EU’s foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas agreed with Trump’s assessment of European spending, saying that “Russia poses an existential threat to our security today, tomorrow and for as long as we underinvest in our defense.”

Many of these critics remain nonetheless alarmed.

“While every president has complained that European countries don’t do enough, there never was a question about American commitment,” said Hodges. “This causes a lot of anxiety.”

In the short term, Trump and key members of his incoming administration have vowed to quickly end Russia’s war in Ukraine, likely impossible without huge territorial concessions from Kyiv. Effectively giving Russia a win would be a signal to the Kremlin that aggression is rewarded and the West has no appetite to intervene, critics say.

“Russia is preparing for a war with the West,” German foreign intelligence chief Bruno Kahl said in a November speech.

For years experts and government officials have accused Moscow of spreading disinformation, launching cyber attacks and using any other means necessary to meddle in the elections of democratic countries.

Though Moscow denies it. Western officials and experts are near united in agreeing that this campaign only seems to be expanding.

Last month, Finnish authorities seized an oil tanker they suspected of having severed undersea power and internet cables. That was among a spate of incidents that prompted NATO to launch operation “Baltic Sentry,” stepping up maritime patrols.

Meanwhile, Western officials said Russia was responsible for sending two incendiary devices to DHL logistics hubs in Germany and the United Kingdom in July as part of a wider sabotage campaign to possibly start fires aboard North America-bound aircraft.

In response, Europe has reversed decades of military underfunding, with most of its big powers now hitting the NATO guideline of 2% of GDP spent on defense. Spending started to increase in 2014 after Russia annexed Crimea, although Trump is widely credited for accelerating it.

On Wednesday, the European Union’s defense commissioner Andrius Kubilius announced that Lithuania intends to spend between 5% and 6% of its GDP on defense in the coming years.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in Feb. 2022 has focused minds further.

In March, the European Union allocated 500 million euros (around $515 million) to double shell ammunition production to 2 million units per year. And 22 countries have now joined the European Sky Shield Initiative, a continent-wide missile defense system designed to protect against Russian attacks.

“Europe must be prepared for the most extreme military contingencies,” a spokesperson for the bloc told NBC News in an email when asked whether the continent was preparing for a worst case scenario of war with Russia. “Put simply: to prevent war we need to spend more. If we wait more, it’ll cost us more.”

Asked if that change was prompted by Trump’s suggestion he may not defend Europe as well as Putin, the spokesperson referred only to the Russian president, whose war in Ukraine they said “challenges the international rules-based order itself.”

For its part, Ukraine’s reaction to the reelection and inauguration of President Trump has been assiduously diplomatic. On Inauguration Day, the country’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy said in a post on X that Trump “is always decisive” and said his second term was an opportunity to “achieve a long-term and just peace.”

Whatever the impetus, “the mindset has changed big time,” said Vytis Jurkonis, who leads the Lithuanian office of Freedom House, an international pro-democracy group.

“We need to make it very clear to the Kremlin that any attack against a NATO member is going to cost and have consequences,” said Jurkonis, who also teaches politics at Lithuania’s Vilnius University.

The Baltic countries of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia are particularly vulnerable, perched on a small peninsula between mainland Russia, the heavily militarized Russian exclave of Kaliningrad and the Baltic Sea.

For decades occupied by the Soviet Union, these now-Westernized states are only now constructing “the Baltic Defense Line,” a frontier hundreds of miles long dotted with anti-tank trenches and pillboxes. Lithuania has already purchased warehouses full of “dragons’ teeth” — concrete pyramids designed to stop tanks — and plans to mine its bridges to the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, its defense ministry told NBC News.

Lithuania recently said it would raise defense spending to 5% of GDP, the highest in NATO and far more, proportionally, than Washington’s 3.4%. That’s still lower than Russia, with the Kremlin effectively reordering its economy along a war footing and committing at least 6.2% of its inflation-hit finances to its military.

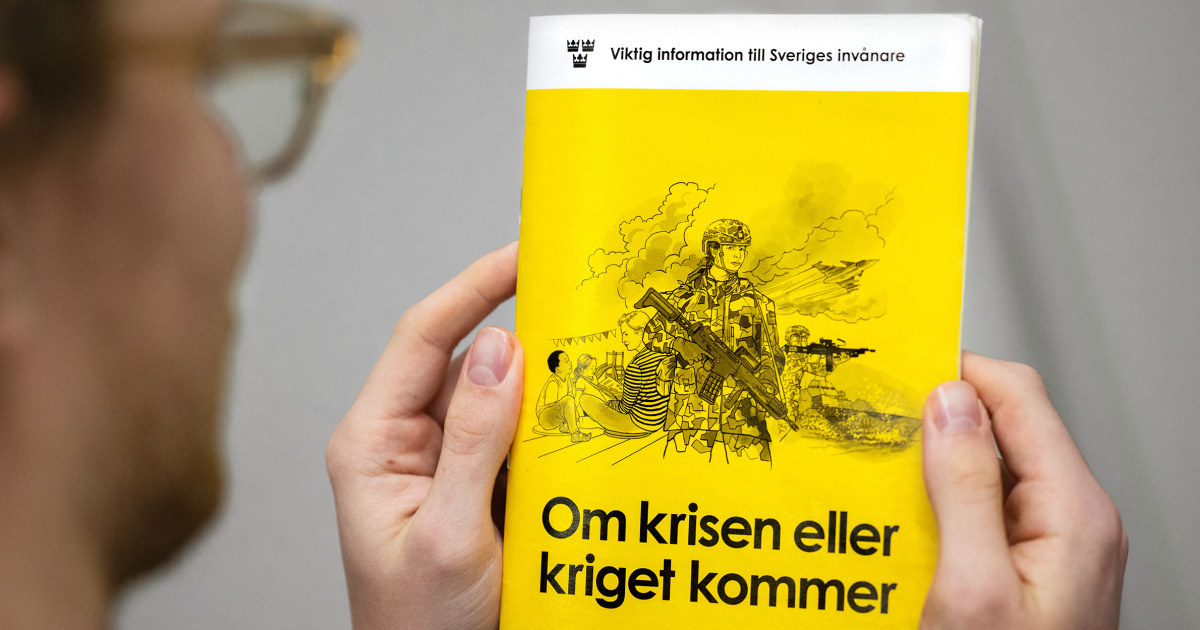

In western Scandinavia, meanwhile, Norway has updated its emergency preparedness booklet that it hands out to all citizens, telling them how much water, food and other supplies to stockpile in case of “acts of war.” The 20-page document has historically focused on extreme weather and accidents, but its most recent version notes that “we live in an increasingly turbulent world” and warns people that “in the event of an act of war, you may be notified that you should seek shelter.

Meanwhile, Swedish church authorities — on guidance from Sweden’s armed forces — have begun looking for extra cemetery space should such a conflict reach their shores. And Germany committed around 100 million euros to reinstate public sirens that were removed when the Iron Curtain fell.

And yet there are plenty of observers who believe that Europe is not doing nearly enough.

Western European countries such as Germany, France and the United Kingdom have only committed “small percentage uplifts to defense budgets, which is nothing like the transformative investment” in Eastern Europe, said Keir Giles, a leading defense analyst at London’s Chatham House think tank.

For Giles, author of “Who Will Defend Europe? An Awakened Russia and a Sleeping Continent,” the problem is that “countries further away are still pretending that war is something that happens to other people.”

What’s more, efforts are further complicated by the political situation. Europe’s mainstream parties are being challenged by populists, who often mix their vehement opposition to immigration with a softer — and sometimes even friendly — stance toward Russia.

That’s a problem for those who argue Russia’s war on Europe has already begun.

“Anybody who isn’t worried hasn’t been paying attention,” said Giles.

Related

A New Book Argues That What Happens in Europe Doesn’t…

Remaking the World: European Distinctiveness and the Transformation of Politics, Culture, and the Economy by Jerrold Seigel “No issue in world

Poland plans military training for every adult male amid growing…

Poland’s prime minister, Donald Tusk, has said his government is working on a plan to prepare large-scale military training for every adult male in response t

2025 European Athletics Indoor Championships: Ditaji Kambundji secures women’s 60m…

Switzerland’s Ditaji Kambundji walked away from the 2025 European Athletics Indoor Championships in Apeldoorn on 7 March with much more than her first Europea

Takeaways from the EU’s landmark security summit after Trump said…

BRUSSELS (AP) — European Union leaders are trumpeting their endorsement of a plan to free up hundreds of billions of