Go to the Mattresses: It’s Time to Reset U.S.-EU Tech and Trade Relations

Contents

EU-U.S. Relations in the Era of China and “Tech Sovereignty” 4

Europe’s Trade Surplus With the United States 6

The Bill of Particulars: How Europe Unfairly Targets U.S. Industry 11

The EU and the China: Brothers in Arms? 25

But Wait, Isn’t the United States Protectionist? 26

Regaining Atlanticism for the China Era. 27

After the United States saved Europe from a Nazi takeover and then for 45 years shielded it from a Soviet invasion, most European policymakers embraced “Atlantic Europe”: a view that Europe needed to be closely tied to the United States, both economically and militarily. But with the fall of the Soviet empire, Europe turned inward to construct a single integrated European Market (EC-92). Now that this project has largely been completed, Europe is shifting to “Fortress Europe,” seeing China and the United States as almost equivalent techno-economic challengers, focusing on technological sovereignty vis-à-vis America while taking a “get as much as you can” approach to trade with China.[1] Many European leaders still want the protection of Pax America, but the leeway to attack U.S. firms and the U.S. economy, and the freedom to engage freely with the Chinese economy—including by selling products to China that the United States forbids with export controls. It is time for the United States to say enough is enough. In doing so, the goal should not be to separate from Europe, but rather to create a more level playing field that enables a new era of deeper integration, grounded ideally in a comprehensive and bold EU-U.S. trade agreement.

Europe is making a strategic mistake of untold magnitude by abandoning Atlantic Europe in favor of Fortress Europe. It would be akin—to use a Lord of the Rings analogy—to Rohan deciding that both Gondor and Sauron posed equal risks. China is just too powerful, and its technological, military, and economic progress are so rapid that if the EU continues to try to go it alone, China will surely succeed in its divide-and-conquer strategy.

However, it would be a mistake for U.S. policymakers to be so desperate for transatlantic concord that they continue to downplay the EU’s techno-economic aggression. It’s time for America to start pushing back by making it clear Europe does not get a free ride in attacking U.S. techno-economic interests while making its own side deals with China.

U.S. policymakers must do more than complain diplomatically to French, German, and other EU policymakers in various dialogues and fora about their efforts to replace goods and services from U.S. tech firms. If the United States tried something similar in a sector in which European firms held most of the market—such as luxury vehicles—the righteous outcry from European defenders of the rules-based global trading system would be immediate and damning. Yet, because European leaders drape their efforts in “European values” and associated privacy, competition, and cybersecurity interests, U.S. policymakers and the media give them a free pass. Even when European leaders repeatedly and consistently say the quiet part out loud—that they want to replace U.S. firms and products—U.S. policymakers still pretend that European partners are acting in good faith, or that they don’t really mean it.

Encouraging Europe to change its approach to U.S. tech has geostrategic implications. Europe is in a different place strategically in relation to China than it was just five years ago. Europe and many other Western nations, such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Korea, would like nothing more than to see the Chinese mercantilist “cat” belled, but they all lack the courage to do it. So, Europe is happy to leave that task to the United States—describing the conflict wrongly as the U.S.-China trade war—so they can avoid punitive retaliation, while at the same time enabling their companies to take U.S. market share in China. Indeed, that is exactly what has happened. While the United States has been taking the heat in fighting back against Chinese innovation mercantilism—a task that benefits Europe perhaps even more than it does America—the EU has moved in and captured what was formerly U.S. market share there.[2] That is not how an ally behaves.

The EU needs to join with the United States to limit China’s techno-economic aggression, and at the same time cease its own aggression against the United States.

Europe is still largely anchored to policies of the past in thinking that it can appease China and maintain its market access, and China won’t eventually target its advanced industries for eradication. European officials often talk in private about concerns they share with the United States about China, but the time for subtlety and inaction has long since passed, because the United States no longer has the ability on its own to potentially force change in China. That time is long past. It will take a concerted and coordinated effort for the United States, Europe, Japan, Australia, Canada, South Korea, and other allies to have any chance of enacting collective defenses against predatory Chinese economic practices. A united front can impose costs on China that together would have the potential to limit its gains in advanced industry market share.

So, the EU needs to join with the United States to limit China’s techno-economic aggression, and at the same time cease its own aggression against the United States. But the United States has not established any real policy to make the EU think there could be tangible consequences for its discriminatory policies. U.S. officials’ approach has been to complain to their European counterparts, not “go to the mattresses,” largely because the U.S.-European policy community argues that America needs the EU for broader strategic interests, especially resisting Russian aggression. While President Trump (and other past U.S. presidents, such as Kennedy) have focused on the threat of withdrawing troops, Europe has always known that was a paper tiger.[3] And so it has proceeded apace.

It’s time for the United States to respond more strategically. Just as the EU seeks to add new instruments to its strategic autonomy toolbox to ensure it can defend itself against countries that abuse its openness—from a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) to mirror clausesto anticoercion instruments—so too must the United States.[4] Congress and the next administration should review U.S. trade defense tools to reflect the rise of European protectionism and digital sovereignty. If left unchecked, Europe’s approach will provide a model for other countries and regions to emulate, which ultimately will lead to the fragmentation of the global digital economy into national and regional “walled gardens.”

The first part of this report provides current and historical context and examples of EU “tech sovereignty” and tech protectionism to highlight that, while not new, it presents a strategic threat to U.S. trade and tech leadership, especially in light of Chinese techno-economic aggression. The second part details the large EU trade surplus with America. The third part details the EU’s array of unfair “innovation mercantilist” practices and policies. The final part puts forth ideas for new, reciprocal tools the United States can develop and use against European firms, technologies, and trade to demand a level playing field.

The transatlantic relationship appeared to get back on track in 2021, with the United States and Europe having put aside disputes over the Airbus-Boeing file (although Airbus had benefited vastly more from its subsidies than Boeing did from its) as well as the steel and aluminum dispute; they also launched the EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council to engage in dialogue on a range of tech issues. However, these papered over even deeper trade conflicts, including in digital industries. There is a clear synergy between the European Commission’s industrial and trade policy strategies, but just not in the open and fair way that Europe so often likes to portray itself in the context of “defending” the rules-based international trading system. U.S. policymakers need to realize that this is neither incidental nor accidental. In fact, it’s central to their approach. The United States needs to treat it as such, similar to how it treats Chinese protectionism.

European policymakers commonly portray digital and tech sovereignty as a strong yet nebulous concept, usually referring to the assertion of state control over data, data flows, and digital technologies, coupled with the replacement of U.S. technology firms with European ones. That it helps them “take back control” and “sovereignty” from mainly U.S. technology firms is not a bug, but rather a central feature.[5] The European Center for International Political Economy has summarized the mix of four factors behind the emergence of technological sovereignty: culture, control, competitiveness, and cybersecurity.[6] In reality, there is only one: protectionism.

While the vague and broad notion about state “control” over data and digital technologies is evident in the various policy issues and debates, it is clear what this means in practice: targeting U.S. firms and products to ultimately replace them with European ones. European leaders such as former German chancellor Merkel and French president Macron explicitly have called for both digital protectionism and data sovereignty in talking about digital and technological sovereignty.[7] It means different things to different officials.[8] For example, the mere fact that data from companies such as Volkswagen were stored on Microsoft and Amazon servers was enough for Germany’s former economy minister Peter Altmaier to state that “in this we are losing part of our sovereignty.”[9] The French minister for economic affairs went so far as to call U.S. “big tech” companies “adversar[ies] of the state.”[10]

For the European Commission, European control largely means that Europe’s policymakers retain the capacity to cater to European firms and advance Europe’s economic interests globally.[11] Ursula von der Leyen, the European Commission president, signaled the EU’s protectionist objectives: “We must have mastery and ownership of key technologies in Europe.”[12] Sabine Weyand, the Commission’s director-general for trade, has echoed that point, arguing there has been a shift in the international order from a rules-based system to a power-based system, and the EU has every interest in opposing that shift because rules-bound international trade protects everyone from arbitrary discrimination.[13] To that end, Weyand says Europe needs to proceed with what she calls a “dual integration” of everything the EU does economically at the international level on one hand, and on the other hand internal EU policies such as industrial policy, internal market policy, competition, or even research policy.[14] In sum, Weyand says, “we must accept this duality, whereby we continue to defend a multilateral order based on rules, but also accept that It is essential that the EU do so from a stronger position.”[15] While European officials defend their conceptualization of “open strategic autonomy” as not being about autarky and self-sufficiency, at every turn when it comes to tech policy, that’s exactly what it is.[16] Even if Ms. Weyand doesn’t interpret it this way, other European officials and political leaders are enacting digital regulations that ultimately reflect this.

Even the recent Draghi report on EU competitiveness reflects this view, even if it often uses code words to mask the EU’s intentions. But with regard to cloud computing, the intent is open: “For reasons of European sovereignty, the EU should ensure that it has a competitive domestic industry that can meet the demand for ‘sovereign cloud solutions.’” [17]

European efforts to undermine American tech leadership and firms are not new, but simply the latest in a long history. Likewise, so is American concern about how to respond. Three quotes from the 1960s reflect this historical point:

He who has technological superiority is master…. [U.S. dominance] risks creating a science gap to the benefit of the United States … a loss of balance from which our economic freedom of action could suffer.… He who has technological superiority is master.… Certainly it would be absurd to systematically oppose oneself to the introduction into a country of a foreign firm which brings in a superior technology and thus contributes to economic progress.… Nevertheless, we do not see how a Nation could maintain its political independence if such penetration becomes generalized.[18]

– P. Cognard, France’s Délégation Générale à la Recherche Scientifique et Technique (1964)

To assist [Europe’s] process by a technological subsidy … might serve to perpetuate bad European practices. Moreover, a substantial part of our favorable trade balance depends on our tech superiority & we should not give it away for nothing.[19]

– Telegram from the Department of State to Secretary of State Rusk (1966)

Political concern in Europe with the technological gap remains high…. They recognize that all of the major factors are ones they must deal with themselves, and there is no longer talk of a ‘Marshall Plan for technology.’ But a deep uneasiness remains … we encountered evidence of rising nationalism everywhere, most clearly in Germany, where the view was expressed, for example, that a major modern State must have an independent capacity to produce computers which are the key to the new society of the electronic age … the fear within Europe of U.S. domination in key European industries is a source of political strain.… Europeans are anxious to benefit the maximum extent from U.S. technological advances while avoiding possibility of American tech domination. This combination of aims has resulted in an ambivalent approach. On the one hand, they are considering essentially protective measures. On the other, they would like the broadest access to US gov-financed R&D.[20]

– Memorandum from the President’s Special Assistant for Science and Technology (Hornig) to President Johnson (1967)

While Europe targeted U.S. firms and trade during the Cold War, the strategic context was clearly different, including the overarching emphasis on “Atlanticism.” Europe depended almost completely on the United States to keep it from being invaded by the Soviets. Today, while Russia is a security issue for Europe, it’s not an existential-level threat. Nor is it something that, if Europe had bothered to build up its own military, Europe could not today handle on its own.

Europe also benefited technologically and economically from U.S. military protection. As the new Draghi report on EU competitiveness notes, “The safety of the US security umbrella freed up defence budgets to spend on other priorities. In a world of stable geopolitics, we had no reason to be concerned about rising dependencies on countries we expected to remain our friends.”[21] It was not the United States that said no to friendship; it was Europe. And there is no word of thanks here; no acknowledgment that the fact that the EU could and did scrimp on defense spending enabled it to spend on commercial technology development at the cost of the United States.

Also, during the Cold War, Europe was not a serious threat to U.S. technological leadership, so it didn’t pose a strategic risk. However, now it is different, and with U.S. (and European) advanced industries under threat from China, the United States cannot afford two-front techno-economic aggression. The Cold War is over, and Europe’s discriminatory tech policies can and do have a sizable impact on U.S. tech firms and their hard-fought leadership positions.

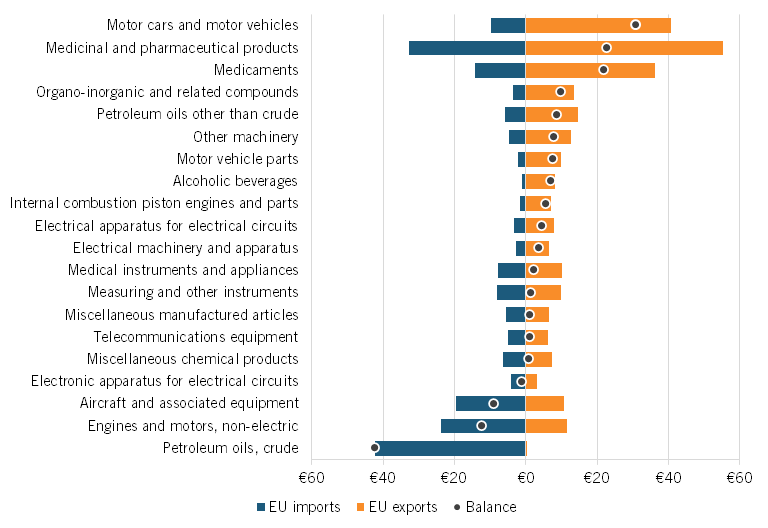

Listening to European policymakers and politicians target U.S. tech firms and products, one might be excused for thinking that the EU must be running massive trade deficits with the United States that are hollowing out its economy. The reality is completely the opposite. In 2023, the EU ran a trade surplus of $208.7 billion with the United States (figure 1). As seen in figure 2, the EU runs significant trade surpluses with the United States in pharmaceuticals and medical devices, motor vehicles and parts, electrical goods, telecommunication goods, chemicals, and instruments. Of the 27 EU nations, all but 7 (Malta, Luxemburg, Croatia, Lithuania, Belgium, Spain, and the Netherlands) runs trade surpluses in goods with the United States. And the country whose officials complain the loudest of U.S. “digital dominance”—Germany—runs the largest trade surplus.[22]

Figure 1: U.S. trade deficit with the EU (billions)[23]

Figure 2: EU trade balance with the United States in goods industries, 2023 (billions)[24]

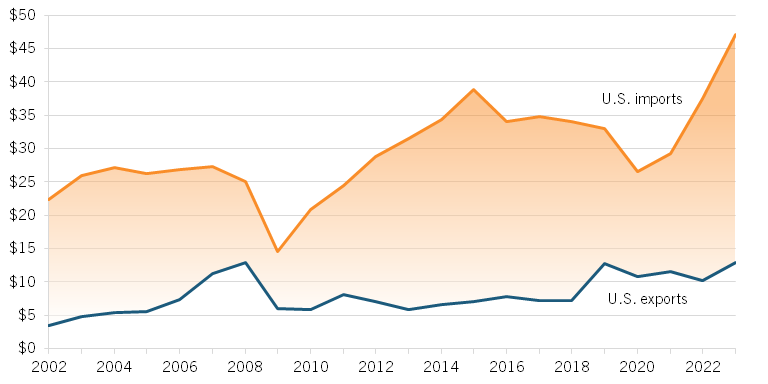

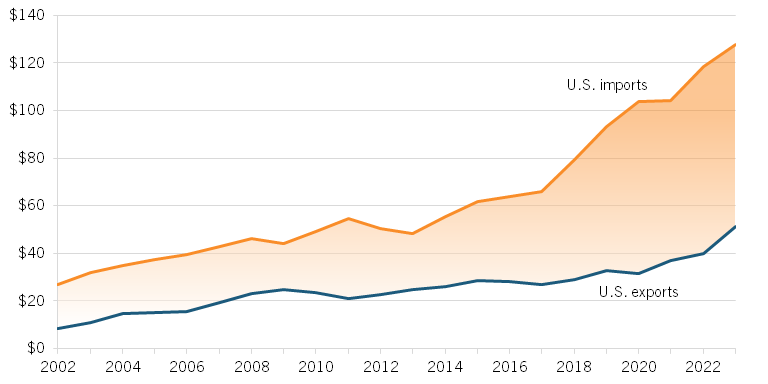

As figure 3 and figure 4 show, the EU has a large and growing surplus in trade in two key categories: automobiles and pharmaceuticals.

Figure 3: U.S. trade deficit with the EU in automobiles (billions)[25]

Figure 4: U.S. trade deficit with the EU in pharmaceuticals (billions)[26]

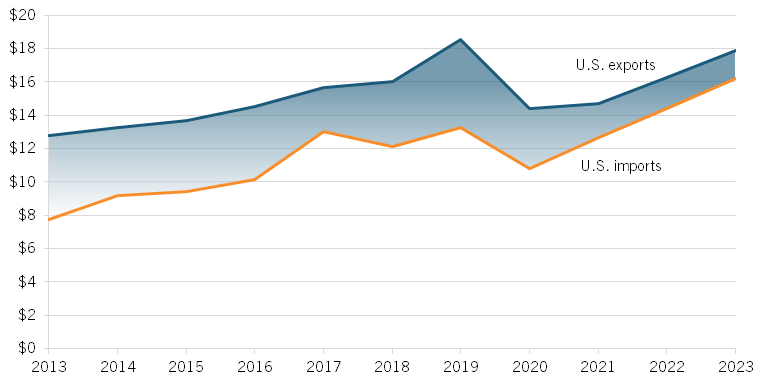

In one of the few areas where the U.S. runs a surplus—digital services—the EU is trying to undermine it. Analyzing the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) “telecommunications, computer, and information services” category in the Balance of Payments guide is a readily comparable measure of digital services across countries. The telecommunications, computer, and information services trade category captures the trade of services included in the broadcast or transmission of sound, images, data, or other information by electronic means, hardware and software, and database services and web search portals, among other services.[27] It shows that transatlantic trade is large and growing, while the U.S. trade surplus in these services is shrinking. U.S. digital services exports to the EU rose from $12.8 billion to $17.9 billion between 2013 and 2023, while EU digital services exports to the United States rose from $7.7 billion to $16.2 billion. (See figure 5.)

Figure 5: U.S. trade surplus with the EU in telecommunications, computer, and information services (billions)[28]

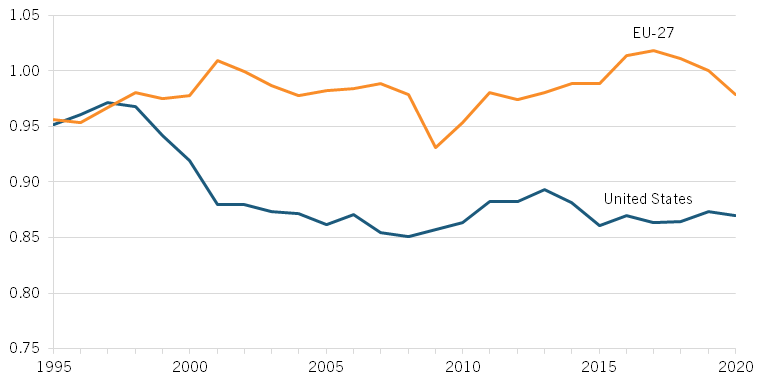

The EU is also outperforming the United States in relative performance in the 10 Hamilton Industries: pharmaceuticals; electrical equipment; machinery and equipment; motor vehicle equipment; other transport equipment; computers, electronic, and optical products; information technology and information services; chemicals; basic metals; and fabricated metals. Relative performance is measured using a location quotient (LQ), which is a measure of industrial specialization relative to the rest of the world. An LQ of 1 means a country’s share of global output in an industry is on par with the size of the global average. Since 1998, the EU’s LQ has exceeded the United States’ rather steadily. (See figure 6.) As of 2020, the LQ of the EU was 0.98 and the United States’ LQ was 0.87, meaning that, while the EU has been able to produce and grow in these strategically important sectors at a pace almost equal to the global average, the United States has fallen behind.

Figure 6: Relative performance (LQ) in the advanced industries included in ITIF’s Hamilton Index[29]

There are a host of ways Europe protects its markets and attacks U.S. competitors, all of which contribute to the large bilateral trade imbalance.

Before detailing EU protections and aggression against U.S. firms and workers, it’s worth looking at two issues: Brexit and digital sovereignty. When the United Kingdom was deciding whether to leave the European Union, both Brexit supporters and opponents agreed that leaving the EU would likely mean a decline in EU market opportunities. But what few pointed out was that this was, ipso facto, an indictment of closed EU markets. If EU markets were truly open, as EU officials like to tout, Brexit should not have affected the United Kingdom’s trade with the EU. But they are not, and that is why between 2014 and 2020 (Brexit went into effect in 2020), the United Kingdom’s trade deficit with the EU was around 26 percent of its exports. By 2023, that had increased to 30 percent.[30] Indeed, one study finds that Brexit reduced trade by 20 percent between the EU and Britain.[31] So much for “free trade” Europe.

The campaign for digital sovereignty is protectionist, pure and simple.

The second issue is the notion of EU digital sovereignty—the claim that leading EU officials make that they should not be dependent on the United States for digital technologies.[32] Let’s be clear what this means. Imagine if Europe said it wanted steel sovereignty. That would mean no steel imports and no foreign steel makers in Europe. How about wine sovereignty? The same. Thus, the campaign for digital sovereignty is protectionist, pure and simple. And we see a host of policies and initiatives that Europe is engaging in to achieve its digital protectionism. Perhaps it is time or American luxury car sovereignty.

EU Lilliputians “tying down” the U.S. tech Gulliver

Europe engages in at least three main types of unfair trade activities related to the United States: discriminatory purchasing; revenue extraction and reduced payments; and discriminatory regulations.

In traditional global trade theory, everyone involved—sellers and buyers—is a utility maximizer. If a seller can buy a foreign product that is as good as a domestic one for a lower price, they do. But like so much of neoclassical economics, the reality on the ground is very different from the idealized reality. Europeans generally are not utility maximizers when it comes to trade. National loyalty plays a role, much more than in the United States. And that accrues to their advantage when it comes to trade flows and industry strength.

Consumer Purchases

One factor that limits U.S. exports to the EU is the nationalistic consumption patterns wherein EU consumers exhibit more loyalty to their own country’s products. For good or ill, U.S. consumers are largely utility maximizers, having almost no loyalty to domestic companies when it comes to making a purchase. Whatever is cheaper is preferred. Europe is different. Many consumers want to buy national. We see this in the long-standing difficulties in getting to a European single market, especially in services. Policymakers blame the failure on the inability to finish creating streamlined EU-wide regulations, even after more than 30 years of trying. But even if Europe could achieve this regulatory harmonization, Europe would still see services localization because so many EU consumers are nationalistic buyers. Many consumers often won’t even buy from European firms outside their country, much less from firms outside Europe.

Take automobiles for example. In Germany, German cars account for around 50 percent of car sales, while French cars account for 5.4 percent.[33] In France, it’s the opposite. French vehicles account for 34 percent of sales and German 21 percent. This has nothing to do with transport costs of the autos from the factory and everything to do with consumer nationalism.

European airlines buy Airbus out of EU loyalty, not out of commercial interests.

Commercial Purchases

We see the same pattern in commercial aircraft, where Airbus is unfairly favored in Europe, not only with a history of massive subsidies, but with nationalistic purchasing by EU airline companies. If market forces were the only thing at play, one would expect to see the same share of Airbus purchases in Europe as in other nations. Yet, a sample of three large European airlines (Lufthansa, SAS, and Air France) shows that their fleets are 70 percent Airbus and 13 percent Boeing.[34] The top three airlines in America are 39 percent Airbus and 61 percent Boeing. Whereas, in “neutral” countries, four large airlines (Air India, ANA, China Southern, and Singapore) have 43 percent Airbus and 53 percent Boeing. Something other than product value is at work here. European airlines buy Airbus out of EU loyalty, not out of commercial interests, and that not only violates free trade as it is conceived by European policymakers, but it also boosts the EU trade surplus, especially with the United States.

Government Purchases

Consumers and (government influenced or controlled) companies are not the only ones engaged in nationalist buying; so is government. Data from the U.S. Government Accountability Office suggests that the EU uses government procurement to discriminate against U.S. firms. Its report estimates that the EU governments awarded $300 million to U.S. firms in government procurement in 2015, while the United States awarded $2.8 billion in procurement awards to EU firms, a level more than nine times higher.[35]

A key component of unfair EU trade practices vis-à-vis the United States is a combination of attempts to unfairly extract revenue from American companies and policies to limit the revenue American companies receive from Europe. We see this in many areas.

Digital Service Taxes

Many EU nations have proffered a fanciful notion, which goes against long-standing corporate tax treaties, that foreign (usually U.S.) digital companies should pay corporate taxes to the EU nations rather than to their home country. As the Tax Foundation has written:

Austria, Denmark, France, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom have implemented a DST. Belgium and the Czech Republic have published proposals to enact a DST, and Latvia, Norway, Slovakia, and Slovenia have either officially announced or shown intentions to implement such a tax.[36]

Digital service taxes are bad policy that provide a thinly disguised effort to target U.S. tech firms. Proponents of DSTs try to justify this tax grab by claiming that users are creating value and therefore that value should be taxed where users reside. (Otherwise, under international corporate tax agreements, foreign nations would not be allowed to tax other countries’ corporate profits.) In fact, users do not create value; companies do. Users consume; digital companies produce.[37]

Furthermore, taxing profits based on where users reside would violate longstanding international agreements by taxing income more than once and imposing an ad valorem tax that primarily targets imports. DSTs obviously discriminate against a narrow set of highly digital industries, mainly search engines, social media platforms, and online marketplaces. Precisely because they fall mainly on U.S. companies, DSTs also likely violate existing trade agreements, as they act as a prohibited de facto tariff. More specifically, the high revenue thresholds that subject a firm to a DST, and the exclusion of certain revenues widely earned by European firms, create de facto discrimination against U.S. digital firms, in violation of the European Union’s national treatment commitment under the General Agreement on Trade in Services.[38]

Meanwhile, the European Commission also has cracked down on individual member states attempting to attract international investment by offering competitive tax policies. For example, the Commission ruled in 2016 that Ireland wasn’t taxing Apple enough and ordered Ireland to collect more than $14 billion.[39] Irish officials defended their tax practices and Apple appealed, but in September 2024 the European Court of Justice ruled in the Commission’s favor, ordering Apple to pay Ireland €13 billion ($14.3 billion) in back taxes.[40]

Exorbitant Fines

At times, it seems as if the Commission is seeking to fund itself by levying exorbitant fines on big American tech companies.[41] For example, in 2017 the European Commission imposed a record-high $2.3 billion fine on Google for, allegedly, manipulating its search results to favor its own shopping comparison service to the detriment of its rivals.[42] In contrast, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission found no “search bias” and concluded instead that Google’s behavior benefited consumers. In 2018, the European Commission doubled down on Google with an even higher fine of $5 billion in another competition law case involving Google’s operating system Android, followed by a 2019 fine of $1.7 billion in a case involving Google’s AdSense online advertising program.[43] In 2024, the Commission levied its third-largest antitrust fine ever: $1.9 billion on Apple.[44] In 2023, the Commission levied a $418 million fine on chipmaker Intel.[45] While the United States and EU try to support domestic semiconductor production, including from Intel, the Commission makes it worse. Qualcomm was hit by a $258 million fine.[46] While China is trying to build up its tech champions, and tear down American, it turns out that it has an ally in Europe. This does not mean that all fines are unfair, but it’s not likely that these finds would be anywhere near as severe if these were EU national champions.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is also another important moneymaker for Europe. As of January 27, 2022, of the 900 fines that EU data protection authorities have issued under GDPR, 7 of the top 10 were against U.S. firms, including an $877 million fine against Amazon and $255 million fine against WhatsApp.[47] According to the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) estimates, between 2020 and 2023, EU governments imposed at least $3.1 billion in fines on U.S. companies under GDPR, equivalent to $29 per American household.[48]

Network Usage Fees

Because the EU depends heavily on U.S. digital platforms, including content providers, it is seeking yet another way to extract dollars unfairly: in this case, a so-called “fair share” policy for Internet traffic that imposes extra fees on U.S. content companies to subsidize European Internet service providers (ISPs).[49] This “unfair share” policy would mandate that content providers, such as Netflix and YouTube, pay fees to European ISPs in return for use of the latter’s bandwidth. No other region does this, for the simple reason that broadband customers pay their own ISP to download bits.[50] Rather than content providers sending data unprompted, it is the ISP’s own customer that is paying to have the data delivered to them. Given this, the “fair” route would be for ISPs worried about too much data use to charge heavy data users more. But going after American content providers is much easier—free money for the EU ISPs and less competition for their own content channels.

In addition to wanting to extract revenue from U.S. companies, the EU is also seeking to limit revenue going to U.S. companies. We see this in at least two areas: pharmaceuticals and computer hardware and software.

Price Controls on Drugs

Through their draconian price controls, European governments refuse to pay their fair share for U.S.-developed drugs. They free ride off American drug companies’ hard work and massive expenditures to develop new drugs. For example, in 2018, if the Netherlands had paid U.S. prices for drugs, it would have paid 122 percent more, while Germany would have paid 87 percent more and France 84 percent more. These price controls mean a higher U.S. trade deficit with Europe because, by definition, EU consumers are getting imports at a mandatory discount. For example, if Spain, Italy, France, and Germany alone had paid their fair share, the U.S. trade deficit with the EU would have declined in 2018 by approximately $75 billion.[51] It also means less biopharmaceutical innovation because drug company revenue and research and development (R&D) is less than it would be otherwise.[52]

Open Source Technologies

The EU pays U.S. companies for hardware and software because these companies have invested billions of dollars to develop intellectual property and high-quality products. The EU doesn’t want to have to pay, so it has long focused on developing open source systems. And let’s be clear: This is about excluding U.S. firms. The EU official open source working group has stated that “the Working Group advocates that this roadmap of activities is supported via coordinated European level actions to avoid fragmentation and ensure that Europe retains technological sovereignty in key sectors.”[53] It went on to note, “An open-source ecosystem needs to be stimulated that can act as an alternative to licensing IPs from non-EU third parties.”[54] This is a euphemism for American companies; in other words, “We don’t want to pay for software imports anymore.”

Europe specializes in regulations that discriminate against foreign goods and services, especially American.

Digital Markets Act and Digital Services Act Discrimination

The EU Digital Markets Act (DMA) should have been called the “U.S. Tech Firms Act.” The European Parliament rapporteur for the DMA, Andreas Schwab, suggested that the DMA should unquestionably target only the five biggest U.S. firms (Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Microsoft).[55] He stated that the DMA’s revenue threshold (to be designated as a so-called “gatekeeper”) should be 10 billion euros and the market value at least 100 billion.[56] He went on to say, “Let’s focus on the biggest problems, on the biggest bottlenecks. So, let’s go down the line—one, two, three, four, five—and maybe six with [China]’s Alibaba … But let’s not start with number seven to include a European gatekeeper to please Biden.”[57] Basically, the DMA and Digital Services Act (DSA) are designed to cover, almost exclusively, U.S. firms and not their European or Chinese competitors that offer similar services.[58] A leaked draft of the proposed EU DSA is quite clear on the intent: “Asymmetric rules will ensure that smaller emerging competitors are boosted, helping competitiveness, innovation and investment in digital services.”[59]

Essentially, the EU shifting the focus of competition intervention from efficiency to market-structure objectives would push competition law in a new direction toward a structural “big is bad” doctrine. Basically, a company’s size (rather than its conduct) would determine whether the new set of ex ante competition rules apply to it. This approach ignores the dynamic competition that gatekeepers bring to the market, the consumer welfare generated by the existing framework, and the innovation and investment incentives necessary to generate future technological breakthroughs.[60] The DMA creates the false dichotomy that a digital market can be separated from a nondigital market, rather than seeing it as simply one of many ways for firms to reach consumers (as a business model and distribution mechanism).

Restrictions on Data Flows

Europe, and its courts, has laid down differing (double) standards when scrutinizing U.S. surveillance practices as compared with what it allows for EU member states.[61] Despite this, the United States consistently engages in good faith efforts to work with European counterparts to create new frameworks and special safeguards and mechanisms for redress for European personal data (that don’t even exist for U.S. citizens).

Edward Snowden’s revelations about the U.S. National Security Agency’s intelligence collection programs have led to successive Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) cases that have restricted and cut off data flows to the United States. CJEU judgments (Schrems I and Schrems II) have invalidated two transatlantic data transfer arrangements: the Safe Harbor Framework and the Privacy Shield Framework.[62] The United States has definitively discontinued a controversial telecommunications metadata collection program exposed by Snowden.[63] It has also enacted other limitations and controls over U.S. surveillance practices.[64] Ultimately, even the National Security Agency’s revised metadata program hasn’t been reauthorized (it lapsed in 2020), and there are no signs that the Biden administration will try to seek legislative reapproval. The United States is developing new oversight and redress mechanisms as part of negotiations with Europe on a successor agreement to Privacy Shield.

If there is an open question whether data transfers from the EU to the United States comply with new European laws, there is a clear answer on China and other authoritarian regimes: Their safeguards bear no “essential equivalence” to EU standards of privacy.[65] Never mind the fact the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) recently conducted a detailed study into government access to data in China, India, and Russia, there are no calls to cut off data to these countries.[66]

At the same time, European governments have received a mostly green light from the CJEU to continue their own bulk metadata programs for national security purposes.[67] The CJEU opened the door a crack for continued bulk metadata retention for national security purposes in Europe in the recent “La Quadrature du Net and Others” judgment.[68] (European policymakers have long deflected calls of hypocrisy, as Article 4(2) of the Treaty of European Union states that “national security remains the sole responsibility of each Member State.”[69]) The CJEU decided that if a member state determines that a “serious threat to national security” exists, it may order service providers to collect and retain bulk metadata, so long as the program is “not systemic in nature.” Soon after, France’s highest administrative court, the Conseil d’Etat, ruled that such a threat existed and that the French government could continue to utilize metadata previously retained for national security purposes.[70]

Meanwhile, Germany has decided to end excessive data retention.[71] At the same time, the EDPB investigated and criticized Europol (the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation) after reports showed it had collected a huge amount of personal and sensitive data.[72] Yet, EU member states and the European Parliament agreed on a new Europol mandate that essentially overruled EDPS’s call for them to delete this data and allowed Europol to continue its data collection practices with new safeguards.[73]

Import Substitution of U.S. Cloud Services

In 2020, the EU created the GAIA-X project and the European Cloud Initiative, in essence, to replace U.S. cloud providers. As usual, Europe tried to drape its efforts in moral values and seemingly upstanding public policy objectives. Europe framed GAIA-X as an “open, transparent and secure digital ecosystem, where data and services can be made available, collated and shared in an environment of trust.”[74] It would create European cloud services and a marketplace to exchange data on conditions that apply “European values” to data protection, cybersecurity and data processing.[75] Yet, from its inception, its true objective—to replace U.S. providers—has been clear. In 2021, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google made up 69 percent of the EU cloud market. Europe’s biggest cloud player, Deutsche Telekom, accounted for only 2 percent.[76] This isn’t the first time France, Germany, and others have tried to forcibly replace U.S. cloud providers and others, such as search (via the French-supported Qwant search engine, which failed and was bailed out by Huawei in 2021).[77]

GAIA-X is a French-German initiative to help build “tech sovereignty”—to encourage firms to store their data with local alternatives to AWS and other U.S. cloud firms.[78] GAIA-X is an organization (not an actual cloud provider) that aims to connect different cloud providers and users so data can move freely between them, while abiding by GDPR’s restrictions. Essentially, Europe hopes that it’ll help local firms such as SAP or Deutsche Telekom to become larger and more competitive. In 2019, France’ Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire stated that France had enlisted tech companies Dassault Systemes and OVH to “break the dominance of U.S. companies in cloud computing.”[79] Indicative of how GAIA-X fits into their plans, in September 2021, France’s digital minister told French GAIA-X participants to “go faster” because they held “in [their] hands … no more no less than a part of France’s digital sovereignty.”[80] In October 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron lamented that Europe was “very late” with its sovereign cloud plans.[81]

Certain EU nations have passed laws requiring cloud computing services to be physically located in their country. For example, in 2022, France enacted updated “sovereignty requirements” as part of a new cybersecurity certification and labeling program known as SecNumCloud. SecNumCloud’s “sovereignty requirements” disadvantage—and effectively preclude—foreign cloud firms from providing services to government agencies as well as to 600+ firms that operate “vital” and “essential” services.[82] The latest SecNumCloud guidance (v3.2, March 2022) retains broad data localization requirements for all data (both personal and nonpersonal) and foreign ownership and board limits, which would effectively force foreign firms to set up a local joint venture to be certified under SecNumCloud as “trusted” and thus able to manage European data and digital services. A prior post for the Cross-Border Data Forum also analyzed this proposal and how it breached EU trade law commitments under the World Trade Organization (WTO) Government Procurement Agreement (GPA).[83] France is leading efforts to embed SecNumCloud’s “sovereignty” requirements in the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity’s (ENISA’s) Cybersecurity Cloud Services scheme, which is under development.[84]

The latest version of SecNumCloud explicitly requires suppliers of cloud computing services to store and process their customers’ data within the EU. This effectively constitutes a ban—or a “zero quota,” in WTO terminology—on the cross-border supply of these services.

Arbitrary Privacy Enforcement

Europe’s selective application of surveillance scrutiny also applies to privacy enforcement. With the death of Privacy Shield, transatlantic data flows face death by a thousand cuts. Privacy activists noyb have filed complaints in all 30 EU and European Economic Area member states against 101 European companies that share data with Google and Facebook.[85] They plan to file hundreds more.[86]

In January 2022, Austria’s data protection authority found that the use of Google Analytics was a breach of GDPR.[87] This is the first ruling in this line of complaints, but it’s not going to be the last. In another, separate, case, a Munich court found that a website owner’s use of Google Fonts violated the plaintiff’s “general right of personality” and right of “informational self-determination” of their IP address under §823 of the German Civil Code. Like the Austrian decision, the only personal data submitted to Google was the user’s IP address. Google’s use of standard contractual clauses could not overcome the risk of U.S. government surveillance, no matter how unlikely or unrealistic the scenario that the U.S. government would seek a European user’s IP address based on their specific interaction with an EU-based website’s analytics tooling or font library. It’s privacy fundamentalism given that it essentially means that any IP address shared, for any reason, in any context, with any U.S. entity subject to U.S. surveillance laws likely also exposes personal data.[88] In February 2022, France’s DPA responded to another noyb complaint and ordered websites to not use Google analytics.[89]

Meanwhile, none of nyob’s complaints were against Chinese, Russian, or other firms using standard contractual clauses to transfer EU personal data. In 2016, Max Schrems stated that firms could use standard contract clauses to transfer EU personal data to China, but not for the United States. Chinese firms could somehow provide assurances that EU personal data could be protected from surveillance in China (where there is no true rule of law and Chinese laws allow extensive state surveillance).[90] DPA investigations into Chinese firms, including Mobike (bike share), BGI Group (genetics), and TikTok (social media), remain limited.[91]

Standards

Technical standards are key enablers of trade and commerce. The norm is for them to be set by industry-led voluntary bodies. However, the EU has long resisted this process because, like China, it wants to manipulate standards setting to favor its own products and firms.

Now in its bid for “digital sovereignty,” the EU wants to ignore international standards-setting processes (and related trade law) for new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI). The EU’s theory is that by setting its own standards rather than following standards developed by international organizations, it can promote European “values” in areas such as data protection, cybersecurity, and ethics.[92] The European Council on Foreign Relations has stated:

If the EU does not set its own standards, it will be forced to adopt standards made by others—who may not share its values. Governance of the internet, including technical governance, is becoming increasingly bifurcated; the danger is that countries will be forced to choose between adopting the standards of a US internet or a Chinese internet, and to thereby give up access to the other market.[93]

A section written for the Commission is even more clear: “While skepticism remains regarding the readiness and willingness of Member States to harness their strengths collectively towards European technology sovereignty, there is no alternative to do so.”[94]

But the logic and process reek of protectionism. By rejecting global technical standards in favor of its own alternatives, the EU is trying to give its firms an advantage over foreign competitors. For example, the EU’s “common specifications” sound obscure and nonthreatening, but they are potentially powerful tools for protectionism. A common specification is defined as “a document, other than a standard, containing technical solutions providing a means to comply with certain requirements and obligations established under (laws/regulations).” This requirement features in recent legislation and regulations for medical devices, cybersecurity, the AI Act, machinery products, and the Data Act.[95] For example, the AI Act specifically mentions it in the context of AI risk management and recordkeeping. In the Data Act, it’s mentioned in relation to building interoperability of common European data spaces. When the Commission creates common specifications for these technologies, it will be mandatory for firms to abide by them to sell into the EU market.

The EU can use common specifications to override or ignore international standards whenever and however it sees fit. For example, it can do so when no harmonized European standard exists or if one needs revisions. It can also do so if one of the three key European standards organizations denies or delays the EU’s request to develop standards; or if the EU simply deems the relevant international standard “unsatisfactory” or does not address European legislative requirements or the EU’s standardization request. The European Commission, at any point over the last few years, could have clarified that common specifications are a tool of last resort and that deference would be given to international standards. Yet, it hasn’t.

The EU could easily engineer a situation to use common specifications, such as setting an unrealistically short deadline for standards or saying they are too slow. For example, the AI Act sets an unworkable two-year deadline for two European standards bodies to develop a broad and complex set of (local) standards.[96] Never mind that this task ignores the years of work a joint committee of the International Standards Organization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) has already done since 2019 on AI standards.[97] In another case, the Commission released the standardization request for the Accessibility Act to the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) at the last possible (legal) moment. It is virtually assured that ETSI will miss the compressed legislative timelines, even though it has already spent years working on relevant standards.[98]

The EU can do this, as common specifications don’t have the critical safeguards of standards developed at international organizations—no transparency, inclusiveness, due process, or appeals mechanism. In contrast, the EU can handpick participants—who may not be technology experts but simply Commission officials—to work behind closed doors (away from scrutiny) to develop common specifications that are mandatory in the EU market. WTO members anticipated that countries could try to impose local technical specifications as trade barriers, exactly as the EU is now doing. That’s why WTO members have committed to using open, transparent, and voluntary standards.[99] The EU and its member states are WTO members and are now violating their commitment.

Weaponized Antitrust

Just as China is doing now, Europe has a history of blocking U.S. mergers that pose a competitive challenge to its own firms. Perhaps the most famous of these cases is the blockage of the GE-Honeywell merger in 2001. The EU also blocked a proposed merger with Sun and Oracle, even though U.S. authorities would have allowed it. It’s impossible to say with hindsight what would have happened had the EU not blocked these mergers. But Sun went out of business, and it’s hard to imagine how General Electric could be any weaker today than it already is. Perhaps if these mergers would have been allowed, Oracle, and especially GE, would be stronger today.

The EU also sought to block to the merger of Boeing and McDonnell Douglas, which the EU opposed because it did not want stronger competition to its continental champion Airbus. As Dorthy Robyn, who helped negotiate the deal in the Clinton White House, noted:

The highest drama occurred in 1997, when the EU’s chief competition authority, a Belgian-socialist named Karl van Miert, publicly threatened to block the Boeing-McDonnell Douglas merger because of the potential harm to Airbus. (Unlike the United States, with its consumer-focused competition policy, the EU is allowed to consider the impact of a merger on domestic competitors.) A potential trade war was averted when DOD sent a decorated Air Force general to Brussels to explain why the merger was important to the U.S. military.[100]

The United States needs to use existing tools better and develop new ones to better target EU protectionism. It needs to be able to “go to the mattresses” and come back with more than a feather duster or toy Nerf gun. The United States does not need to use all its tools at once, but it should start enacting some short-term measures and putting in place the legal and administrative reforms to create new tools for the future (in case they’re needed). In other words, EU policymakers need to know there will be real negative consequences for their continued actions.

At the heart of the United States’ approach to European trade should be a focus on the core principles of the multilateral trading system at the WTO: transparency, due process, national treatment, and nondiscrimination. If European laws and regulations don’t live up to these core principles—that the EU itself advocates for in supporting the WTO and the global trading system—then it should trigger a ratcheted and targeted response by U.S. policymakers. It’s time that the next administration hold the EU up to its own standards, especially in terms of its treatment of U.S. firms.

Doing more than complaining to European officials will likely elicit retaliatory action from Europe. But Europe can’t continue to have it both ways: benefiting from cooperation, military assistance, and open trade with the United States while still targeting U.S. firms and trade.

It’s time that the next administration hold the EU up to its own standards, especially in terms of its treatment of U.S. firms.

The federal government needs to use both offensive and defensive trade policy measures.

Amend, and Use, Section 301 to Target Digital Trade Issues

The next Congress should update a main trade defense tool—the Trade Act of 1974—for the digital era by amending it so that it can respond to the type of barriers (digital) that are central to modern trade. Section 301’s traditional use of tariffs makes it easy to apply to 20th century trade in goods, but it needs to be amended to create new legal and administrative mechanisms and tools to target service providers. Although Section 301 mentions fees and restrictions on services, it should be amended to detail the mechanism (in terms of responsible agency) and process (in terms of the action, such as licensing, certification, or legal judgment) whereby the administration imposes specific retaliatory measures on a foreign service provider. For example, it should be amended to create a reciprocal joint venture requirement wherein French, German, and Chinese tech and cloud firms would be forced to set up local joint ventures with equivalent ownership and control restrictions that U.S. firms have had to set up in their respective countries.

Pursue a Section 301 Investigation of the DMA and Other Digital Sovereignty Initiatives

The next administration should use Section 301 to initiate an investigation of the DMA, as it is among the most clearly egregious examples of European policymakers targeting U.S. firms. There is a clear case to be made that the DMA would meet the standard for action under section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. However, an investigation could be broader and include other EU digital sovereignty initiatives, such as discriminatory cybersecurity regulations and exclusively European cloud initiatives. The Biden administration could enact retaliation via tariffs on imported goods (the traditional use of Section 301), taxes or restrictions on EU digital service companies doing business in the United States (a new use of Section 301), and restrictions on other EU service providers, such as accounting firms, air carriers, media companies, automotive companies, aerospace companies, and others.

Use Department of Commerce ICT Service Reviews to Cover EU Firms

The Department of Commerce could interpret new rules regarding the use of information and communications technology (ICT) goods and services by foreign adversaries to apply to transactions with EU firms that use ICT goods and services with those same adversaries. The Rule (86 FR 4909) on Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain provides a framework for Commerce to unwind ICT services transactions with foreign parties that “(1) involve ICTS [Information and Communications Technology and Services] designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied by persons owned by, controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of a foreign adversary [defined to include China, Russia, Iran, Cuba, Venezuela, and North Korea]; and (2) poses an undue or unacceptable risk.”[101] The rule allows Commerce to review transactions involving a wide range of ICT products and services, including data hosting and computing of sensitive personal data.

Europe is well within the potential scope of application given the Commerce Department’s focus on ensuring that the rule can be used as effectively as possible. Commerce has ruled out categorical exemptions of specific industries or geographic locations, although the secretary of Commerce may consider this possibility in the future. Wholesale exemptions of industries and geographic locations would not serve the rule’s intended purpose of securing the ICTS supply chain because such exemptions would contradict the Commerce Department’s evaluation method for ICTS transactions. Such exemptions would apply to foreign adversaries’ whole classes of ICTS transactions outside the scope of evaluation under this rule.[102]

Impose Mirror Taxes on Countries That Impose Digital Service Taxes

Europe’s (and others’) use of digital service taxes to single out American tech firms for blatantly discriminatory punishment needs a clear response. The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) has already released a detailed Section 301 report on the issue, including the threat of retaliation.[103] As Gary Hufbauer at the Peterson Institute for International Economics suggests, the United States should amend the Internal Revenue Code to enact a tax on large foreign firms that extracts funds in mirror-image fashion to the discriminatory digital tax on U.S. firms.[104] Section 891 of the Internal Revenue Code (enacted in 1934) provides the legal authority for the president to retaliate against foreign discriminatory or extraterritorial taxes. It allows the president to enact taxes, and to ratchet them up, on foreign citizens and firms. It has never been used. Congress could adapt it for the modern era in mandating a tax on the global revenues of large firms based in France, Italy, and other DST countries when those firms sell goods or services in the U.S. market. The tax could be legislated to expire upon either of two events: agreed international rules that subject tech giants to taxation in countries reached by their platforms or repeal of an individual country’s own DST tax.[105]

Create a Cause of Action Allowing U.S. Firms to Sue for DMA-Mandated Disclosure of Trade Secrets and Confidential Information

The DMA specifically targets not only U.S. firms but also core components that make up their competitive and innovation goods and services. The DMA includes a provision requiring “gatekeepers” to disclose certain search engine data (rankings, search data, click and view data) to third-party providers of online search engines upon request and on fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory (FRAND) terms. It’s essentially state-directed forced trade secret disclosure (vis-à-vis China’s forced technology transfers).

Congress could create a cause of action in U.S. courts for U.S. firms to obtain financial damages from EU companies that use this provision to obtain their trade secrets and other commercially sensitive information. This would essentially act as a blocking statute to counteract discriminatory EU digital laws and regulations. While the U.S. firms that would potentially use this are small (given the EU is targeting just five firms), it would send a clear signal that there are consequences for unfair and unjustified state intervention into a firm’s trade secrets and competitive position.

Limit Transfers of U.S. Citizens’ Data to the EU

Thierry Breton, the EU commissioner for internal market, has argued that “European data should be stored and processed in Europe because they belong in Europe. There is nothing protectionist about this.”[106] No, actually there is. As such, if the United States and the EU cannot work out an easy-to-administer process by which data can flow seamlessly across the Atlantic, the United States should adopt a similar approach to Europe’s: limiting the transfer of U.S.-person data to European companies in Europe.

Limit Federal Procurement Opportunities for EU Firms

The U.S. president has the legal authority to withdraw the Trade Agreements Act waiver for the EU with respect to the Buy American Act program, or for particular categories of EU products/services or suppliers (such as certain technologies or digital services).[107] For example, the president can add or remove end-product categories that are subject to trade agreements in lieu of Buy American Act preferences in Department of Defense (DOD) acquisitions.[108] Similarly, the United States can adjust discretionary preferences under the Foreign Military Sales program. Ultimately, the end result would be similar to how the United States purposely excludes adversaries such as China and Russia from ICT supply chains and procurement (and how U.S. firms and products are excluded from China’s and Russia’s procurement markets).

Scrutinize Critical Exports to the EU by Removing Their “Favorable” Designation

U.S. policymakers could exclude EU firms from U.S. funds in order to boost U.S. production of medical goods and services. The United States should not be inadvertently bolstering the EU’s plan for “strategic autonomy” in the area of medicine to reduce “strategic dependencies” and foster production and investment in Europe. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ 100-day supply chain review calls for boosting U.S. production through “a blended mix of targeted investments and financial incentives.”[109] Also, to combat the EU’s significant trade surplus with respect to pharmaceuticals and incentivize domestic production, the United States could consider imposing tariffs or other import restrictions on EU pharmaceuticals.

Exclude EU Firms From the U.S. Defense Industrial Base

The Biden administration should move ahead with proposed plans (by DOD and Congress) to amend the Defense Production Act to expand the list of countries in which the U.S. government can make industrial investments to produce certain products that support national defense requirements, such as microelectronics and medical supplies. Currently, only the United States and Canda are on the list, but DOD wants to include the United Kingdom and Australia. Until the EU makes clear its commitment to once again embrace Atlanticism, as opposed to fortressing Europe, the administration should ensure that the EU and its member states are not included.[110]

Retaliate Against Hypocritical Standards for Government Access to Data and Surveillance

The United States should create its own capability to identify and respond to other countries that fail to provide comparable or reasonable safeguards, frameworks, and agreements around government access to data and that otherwise misuse concerns over foreign government access to data to selectively enact restrictions that target U.S. firms. This would support ongoing discussions at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on the issue of government access to data. Whether it’s national security- or Europol-motivated access to data, EU member states, leaders, and parliamentarians realize that there is a real and legitimate trade-off with privacy at home.[111] It’s time the United States makes sure it recognizes that this also exists internationally, and that selective application of concerns will entail costs. Doing so would ensure foreign countries, especially European ones, could not hypocritically call for changes in the United States that they themselves don’t provide at home and only selectively scrutinize certain countries’ practices.

The United States, especially after the 2015 passage of the USA Freedom Act (which was the biggest pro-privacy change to U.S. intelligence law since the original enactment of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in 1978) and other post-Snowden reforms, has been rightfully described by Oxford expert Ian Brown as “the baseline for foreign intelligence standards.”[112] Independent analyses, including by the EU’s own Fundamental Rights Agency, have documented great variations in rigor among privacy safeguards against surveillance conducted by EU member states under domestic legal authorities.[113]

The United States should create an inter-agency body, hosted by Commerce Department, that identifies whether EU member states and other trading partners have similar or equivalent safeguards and oversight for government access to data as the United States does. The Biden administration’s Executive Order (EO) on Protecting Americans’ Sensitive Data from Foreign Adversaries is relevant, but it mainly targets China’s (and Russia’s) ability to access U.S. data. But the basis for this EO and its many processes and outcomes are applicable to Europe’s selective and hypocritical application of concerns over government access to data.

President Biden’s Executive Order number 14034 on “Protecting Americans’ Sensitive Data from Foreign Adversaries” provides for cabinet-level assessments and future recommendations to protect against risks from foreign adversaries’ access to U.S. persons’ sensitive data and involvement in software application supply and development; and also the continuing evaluation of transactions involving connected software applications that threaten U.S. national security.[114] It is, in part, based on the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C. 1701 et seq.) (IEEPA). The ongoing emergency that President Trump previously declared in Executive Order 13873, “Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain,” arises from a variety of factors, including the continuing effort of foreign adversaries to steal or otherwise obtain United States persons’ data. Biden’s EO states that the “continuing effort by foreign adversaries constitutes an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States … To address this threat, the United States must act to protect against the risks associated with connected software applications that are designed, developed, manufactured, or supplied by persons owned or controlled by, or subject to the jurisdiction or direction of, a foreign adversary.”[115]

The Biden administration should do this via a subsequent, complementary, EO that tasks the secretary of Commerce—in consultation with the secretary of State, secretary of Defense, attorney general, USTR, secretary of Health and Human Services, secretary of Homeland Security, director of National Intelligence, and heads of other agencies as the secretary of Commerce deems appropriate—to work together on the issue. Similar to USTR’s approach to investigating and responding to digital service taxes, the United States should use this investigation into what oversight and safeguards other countries use with regard to privacy and surveillance—and how these compare with the United States’—and identify countries that misuse concerns about privacy, cybersecurity, and surveillance to enact restrictions that target U.S. tech firms and products, while not applying similar scrutiny and restrictions on local and other foreign firms and countries.

In the event the United States finds that countries are unfairly targeting U.S. firms, it could draw up tariffs and other regulatory restrictions to enact against these countries and their own tech firms, but suspend them pending the reasonable conclusion of a U.S.-EU CLOUD Act agreement, negotiations over government access to data at the G7 and OECD, or both.[116] Signing up to, and abiding by, a CLOUD Act agreement and potential OECD framework on government access to data would become the basis for ensuring continued market access to the U.S. digital economy given it would represent an international best practice (and genuine, good faith effort on behalf of governments on what is a global issue) on an issue that is often used to disguise digital protectionism.

At first glance, what is remarkable about the list of EU actions against the United States and its tech firms is that it bears a striking resemblance to what China is doing. Both want to weaken the U.S. tech economy so that they can boost their own strength. Both want to displace U.S. tech companies through open source. Both put severe price controls on drugs. Both use antitrust to weaken U.S. firms. Both use government procurement to favor their own firms. Both impose significant fines and other penalties on U.S. firms through antitrust. Both pressure their firms to buy local. Both limit data flows. Both push for open source technologies to become free of American imports. Both use government funding to prop up competitors of U.S. firms. Both pressure U.S. firms to set up data centers there. To be sure, China is much worse in the applications of these tools, but the EU is engaged in similar behavior against the United States.

And both are seeking strategic independence from the United States. The Draghi report states, “These dependencies are often two-way—for example, China relies on the EU to absorb its industrial overcapacity—but other major economies like the US are actively trying to disentangle themselves. If the EU does not act, we risk being vulnerable to coercion.”[117] Yes, the United States is trying to disentangle itself from China, an authoritarian state bent on global techno-economic domination. If Europe were astute, it would be doing the same. But the United States is not trying to disentangle itself from the EU. Moreover, the idea that the EU is vulnerable to U.S. coercion is both nonsensical and offensive. Given that the United States has protected Europe with its military, America has had plenty of opportunity to coerce the EU and never has.

EU officials and experts love to trot out the canard that the United States is protectionist. I have a one-word answer for this question: no. But I will expand it to a six-word answer: $904 billion U.S. current account deficit.[118] To say that the United States is protectionist when it runs the world’s largest trade deficit is, frankly, laughable. The EU? It currently runs an account surplus with the rest of the world. Case closed.

But what about Buy America and Buy American provisions that favor U.S. made goods in federal government procurement? Again, a $904 billion current account deficit with the world, and a $125 billion goods and services trade deficit with EU. But even if this were not the case, as previously cited, the U.S. government already procures nine times more from the EU than vice versa, so the EU can start complaining about Buy America when that ratio is down to one.

And finally, the big kahuna: the IRA and CHIPS Act subsidies for investing in America in clean energy and semiconductor facilities. First, these kinds of subsidies are par for the course now, being rampant in most Asian nations. Like it or not, the only way to assure domestic production in these kinds of critical industries, especially to compete against the Chinese juggernaut, is to provide investment subsidies. Rather than complain, the EU should wake up and get in the game. And of course, EU firms are eligible for these subsidies. Oh, and let’s not ignore that massive launch aid given to Airbus, without which the company would not have survived?[119]

This all feeds into the popular narrative that “the United States turns its back on the world.”[120] According to this tale, America was the epitome of global openness and with Trump it became a villain of protectionism, with Europe left to hold aloft the beacon of free trade. It is a reassuring narrative to Europeans, but it is false. First, if the this is true, why is that the U.S. goods and services trade deficit with the European Union as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) actually increased from 0.43 percent in 2016 0.45 percent in 2023?[121] How exactly is that protectionist? Again, if and when the EU runs a trade deficit with America, we should talk. Otherwise, stop the posturing.

After criticizing China, Mario Draghi, author of the new report on EU industrial policy, had the audacity to put the United States in the same camp as China, stating, “The US, for its part, is using large-scale industrial policy to attract high-value domestic manufacturing capacity within its borders—including that of European firms—while using protectionism to shut out competitors and deploying its geopolitical power to re-orient and secure supply chains.”[122]

Mr. Draghi, please explain and give examples of how the Untied States has shut out European competitors from the U.S. market. Moreover, is it using its geopolitical power to re-orient supply chains out of China? Are you really saying that you oppose this? That you trust China and believe that it is playing by the rules and has no designs on becoming the new global hegemon?

Europe is right to focus more on competitiveness, and hopefully the forthcoming Draghi report will include useful recommendations that get implemented. But that strategy should not be one focused on “fortress Europe” against both China and the United States, for not only would that be extremely shortsighted for Europe, but it would also be turning its back on the West and democracy. It is time for Europe to realize that China is the core threat to the West, and that it should be supporting, not attacking, U.S. efforts to limit and protect against the damage from Chinese innovation mercantilism. The goal should be Western competitiveness, not European.

Some argue that we must do whatever we can to not alienate the EU so it can help address the China challenge. But that misses the point. As long as the EU views the United States and China is in the same camp as competitors that limit EU technological sovereignty, any efforts by the United States will fail. The EU will not join the fight, preferring to take advantage of the commercial conflict between the United States and China—and it will not roll back its protectionist and mercantilist actions toward the United States.

The United States needs to be clear that the EU must roll these actions back and join with the United States in a new, democratic, free-trade bloc. And if it fails to do so, the United States will respond with countervailing economic force, But if Europe does decide to join with America, then both sides should do whatever they can to strengthen the alliance. This should start with an EU-U.S. trade agreement, which eliminates all tariffs on products traded between the two nations and eliminates virtually all nontariff barriers. This would require EU leadership ignoring the anti-American civil society groups in Europe and both their often nonsensical and antiscientific concerns (such as chlorinated chicken, GMO crops, proposed bans on silicones) and their outright lies about investor-state dispute settlements. The fact that EU interest groups tanked the prior deal is one more bit of evidence of how closed EU markets really are, as well as how unserious the EU is in addressing the critical issues of today’s global economy,

Any new, comprehensive trade agreement between the United States and the EU should lay out a cooperative formula for export controls to China, import restrictions on China, commercial counterintelligence sharing vis-à-vis China, and finally, deep advanced technology cooperation, especially in critical industries under threat by China.

Since the 1960s, Europe has viewed U.S. IT leadership with alarm. As French economic journalist Jean Jacques Servan-Schreiber wrote in his 1968 bestseller, The American Challenge, “One by one, U.S. corporations capture those sectors of the economy most technologically advanced, most adaptable to change, and with the highest growth rates.”[123] Like today, Europeans characterized the challenge in dire terms: “a seizure of power,” “invasion,” “domination,” “counterattack,” and “industrial helotry.”[124]

But unlike for today, Servan-Schreiber didn’t call for an attack on U.S. firms; he called for Europe to get its house in order: build a single market, fund advanced technology R&D, and expand university enrollment, particularly in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math). He eschewed any talk of punishing or rejecting U.S. investment. In fact, he wrote, “Nothing would be more absurd than to treat the American investor as ‘guilty’ and to respond by some form of repression.” While the Draghi report does not go as far as Servan-Schreiber did in eschewing anti-American policy, it is far in the right direction.

But to date, EU officials have done little to remedy the EU’s problematic and protectionist policies, in part because they know that the transatlantic “blob” (the network of think tanks, influencers, companies, and government officials) committed to a harmonious cross-Atlantic relationship will veto any tough action. It’s time to end that, at least in the United States. The next administration should make it clear that unless the EU effectively addresses a significant share of these trade barriers and anti-U.S. policies, the U.S. government will take firm action.

And the faster that the EU can recognize that the challenger is not America but rather China, the sooner we can get on with forging a much more productive relationship. However, should the EU continue to choose to go it alone, seeing the United States and China each as threats, it will lose. Its only hope is a strong alliance with the United States, and that will not happen as long as the EU continues to discriminate against U.S. companies.

Finally, if the United States makes it clear that it will no longer accept this kind of discriminatory EU behavior, the EU hopefully will realize that it has to modify its approach. Then and only then can we reestablish a strong Atlanticism for the 21st century—one based on much deeper cooperation, including in advanced technology—in order to not succumb to the Chinese advanced technology challenge. The idea that the EU can be competitive in advanced industries on its own, and against both China and the United States, is ludicrous. China, not the United States, is the threat to Europe. This is equivalent to Europe saying in the height of the Cold War that it wanted to be unaligned and compete militarily and economically with both the Soviet Union and the United States.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank ITIF’s former associate director of trade policy, Nigel Cory, for providing input to this report. The author also thanks to Megan Ostertag for her help with data collection and analysis. Any errors or omissions are the author’s responsibility alone.

About the Author

Dr. Robert D. Atkinson (@RobAtkinsonITIF) is the founder and president of ITIF. His books include Technology Fears and Scapegoats: 40 Myths About Privacy, Jobs, AI and Today’s Innovation Economy (Palgrave McMillian, 2024), Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (MIT, 2018), Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (Yale, 2012), Supply-Side Follies: Why Conservative Economics Fails, Liberal Economics Falters, and Innovation Economics Is the Answer (Rowman Littlefield, 2007), and The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation That Power Cycles of Growth (Edward Elgar, 2005). He holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.