Fascism shattered Europe a century ago — and historians hear echoes today in the U.S. – Berkeley News

It was a time of historic change, and society was buckling under the stress. There had been a war, then a deadly pandemic. Economic crisis was constant: Racing inflation, unemployment and changes in technology provoked extreme economic insecurity.

But a leader emerged who understood the fear and humiliation felt by his public. He validated their rage and focused blame on a scapegoat. He pledged to make the nation whole again, to return it to its rightful glory. Much of the population, suffering so profoundly from the shock of loss and change and insecurity, embraced the leader as a sort of messiah. They accepted political violence, even welcomed it, and they turned away from democracy.

The scenario is historically accurate, but to which country does it apply? Italy in 1923? Germany in 1933? Or the United States today, nine weeks before the presidential election?

The answer, according to some UC Berkeley scholars, is that the scenario applies generally to all three: Italy during the rise of Benito Mussolini, Germany as Adolph Hitler maneuvered his way into power, and the United States, deeply polarized and tense as the MAGA movement led by former president Donald Trump moves to reclaim the White House.

UC Berkeley photo

None of the scholars forecast an imminent turn to autocracy in the U.S., and all were careful to say the U.S. experience today is in important ways different from devastating conditions that preceded the rise of European fascism in the 1920s and ‘30s. But in a series of interviews, experts who have studied the political and economic history of Europe traced dramatic and deeply troubling parallels between that era a century ago and this fraught American moment.

As in Europe after World War I, “there’s kind of a disdain for democracy,” said John Connelly, the eminent historian of modern Europe. “There’s a willingness to think of going beyond the technicalities of a democratic system in order to solve problems. There’s a longing — there’s a respect for strong leadership that many believe is lacking in a standard liberal democracy.”

Brittany Hosea-Small for UC Berkeley

The view was not unanimous. Jason Wittenberg, a political scientist who has studied European politics and dictatorships, insisted that the U.S. military and other institutions would not succumb to strongman rule.

“My bottom line is that fears about Trump are not entirely unfounded, but they’re massively overblown,” Wittenberg said. “Yes, he could do damage. But in the worst-case scenario, there’s just no plausible circumstance under which an illiberal government could be implemented. There’s no way it could happen.”

And yet, the cautious consensus that emerged from the interviews is that U.S. democracy is more vulnerable today than it has been since the Civil War more than 160 years ago. Several scholars believe the public’s frustration and polarization, incidents and threats of right-wing violence, and a radical new Supreme Court ruling granting presidents broad immunity from the law could precipitate a break with democracy.

Courtesy of AJ Solovy

Such conditions undercut democracy in Italy and Germany, and the scholars see some of the same troubling signals here today.

Because the forces of history are so complex, “I’m wary of trying to draw exact parallels,” said AJ Solovy, a Ph.D. student whose research is focused on German fascism. “But the Third Reich and Germany in the 1930s offer important, useful paradigms through which to understand this particular moment in the U.S. Even if there is not a one-to-one match, the themes that emerge — insecurity, crisis, a sort of existential political angst — can help explain why so many people are attracted to the MAGA movement.”

Put another way: It’s not enough to look at how the leaders of anti-democratic movements might be alike. Instead, it’s essential to look at the broader conditions that allowed for the rise of those movements.

Condition No. 1: An era of extraordinary instability, loss and perceived humiliation

Any discussion of 20th century fascism in Italy and Germany begins with World War I. The war brought a level of death and devastation that had never been seen before. New weapons technology turned portions of Europe into a killing field. Relentless shelling barrages didn’t merely maim and kill, but obliterated bodies on a mass scale.

Germany lost the war, and Italy was on the winning side. But for both, the aftermath was devastating: Millions dead and wounded. The Spanish flu, and thousands more dead. Hyperinflation, unemployment, widespread hunger. Grave polarization and political instability. And then, the Great Depression.

Collection of the Imperial War Museums, United King

Leaders, the military and the people in both nations felt crushed and humiliated.

The traditional order was dissolving, and crisis was constant. The Russian Revolution appealed to many, but also provoked widespread fear of communism. Women were gaining political emancipation. Film and radio were extending their reach. Modern art was rejecting the subjects and styles of the past. Political and culture wars raged across the landscape.

In both countries, the scholars said, people suffered from a profound sense of dislocation. Lawrence Rosenthal, a scholar of Italian fascism and the founder of the UC Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies, described it as a violent break between past and future that affected tens of millions of people.

Both Italy and Germany were deeply divided between advanced industrial areas and rural regions that seemed stuck in a feudal era that hadn’t changed in centuries, Rosenthal said. He imagined the experience of young Italian soldiers who lived through the war and the flu pandemic.

“When the war is over, they go back to their villages, their hometowns, and they don’t fit anymore,” he said. “Everything has changed.”

After the horrors of war, they have changed, too — they’re lost, alienated, dispossessed. What remained was their shared experience with other soldiers, “the brotherhood of the trenches,” Rosenthal said. “And this was a potential mass base for fascism.”

In such tectonic shocks, the scholars see strong but uneven parallels between Europe in the 1920s and ‘30s and the U.S. today. COVID parallels the Spanish flu. The U.S. is divided between regions thriving in the information economy and chronically depressed Rust Belt and rural regions. But while the U.S. has suffered from inflation since the pandemic ended, hyperinflation in Germany was almost 1,000 times worse. And the U.S. has no recent experience comparable to World War I or the Depression.

Still, questions remain: Even if Americans have not been exposed to such a shattering experience, is it possible that a series of smaller shocks could cause similar trauma? And could this trauma fuel an authoritarian political movement in the U.S.?

Condition No. 2: In a time of traumatic upheaval, some people seek order at any cost

Ulrike Malmendier, a behavioral economist at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, has conducted influential research into how the Great Depression and other traumatic experiences shape people’s worldviews and decisions, even decades later.

Malmendier said trauma researchers generally categorize two sorts of experience: “big-T trauma,” such as a war, extreme economic crisis, sexual assault or terrorist attack; and “small-t trauma,” such as the modest, but painful, “paper cuts” that we accumulate in daily life.

Think about food insecurity in a time of inflation. “It’s not that you have no access to food and you’re starving,” she said. “But you have this insecurity that food might not be available, or you might not have enough, because prices are rising.”

Changing technology, changing demographics and the shocks of economic globalization can have a similar effect.

Malmendier explained: “People think, ‘Something around me isn’t quite as it used to be. My work skills might not be as valuable as they were. I’m constantly worrying, ‘What does that mean for me?’

“With technological change, or demographic change, the constant worry of how you fit into this place might be as big as if there was a war — ‘I now live in a different environment. I’m feeling displaced.’”

In effect, Malmendier said, trauma rewires our brains. Even modest change can be traumatic and can trigger a primal impulse to avoid further shocks. People might imagine that things would be better if only they could return to the order of the good old days.

Now consider the U.S. experience since the start of the 21st century: The 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 were followed quickly by wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that lasted for years and ended in stalemate. The Great Recession in 2008 and 2009 wiped out savings and drove a spike in unemployment.

The nation’s demographics were changing. While many celebrated the election of Barack Obama as the nation’s first Black president in 2008, and the nomination of Hillary Clinton as the first woman to win a major-party presidential nomination in 2016, many others were deeply resentful. For some, resentment extended to the legalization of same-sex marriage and the expansion of rights for transgender and nonbinary people.

The era has featured almost unchecked random mass shootings and declining affiliation with traditional religion. Technological change has been rapid and disruptive; the internet, smartphones and social media have overwhelmed us with disinformation. In the aftermath, political and social polarization has steadily deepened.

Doug McClelland

Chronic insecurity can be a powerful driver of anti-democratic movements, said David Clay Large, a senior fellow at the Berkeley’s Institute of European Studies.

“Social change — gender, art, politics, class — leads to insecurity,” said Large. “People get used to certain norms, a certain place in the world. Then their world is turned upside down. In Europe in the ‘20s, it happened quickly. In this country, it’s been more gradual.

“There is a feeling of having lost something, sometimes a mythologized or romanticized past that people claim they’re missing. You can say that’s nonsense, but they still feel it. And that’s important.”

Malmendier hasn’t studied anti-democratic movements, but she sees a connection: Once this sort of trauma gets wired into the brain, people can believe it’s “very, very likely that the next traumatic event is just around the corner,” she explained. “They might make an exaggerated attempt to avoid being put in this painful situation again.

“That is where you might see a link to extremism, or maybe populism.”

Condition No. 3: A strongman leader appeals to the fear and rage of his public

In simple terms, populism is a social movement that seeks to turn back the clock, by extreme measures, if necessary. Nationalism is a natural extension, an effort to return the nation to its imagined former greatness.

Both are fueled by a widespread sense of loss and humiliation, and by grievance and resentment. There’s a sense, the scholars said, that modern ways aren’t serving the needs of the masses, and the masses need to seize power and restore order and justice.

In such conditions, Connelly and others said, people can turn away from democracy — and toward an authoritarian leader.

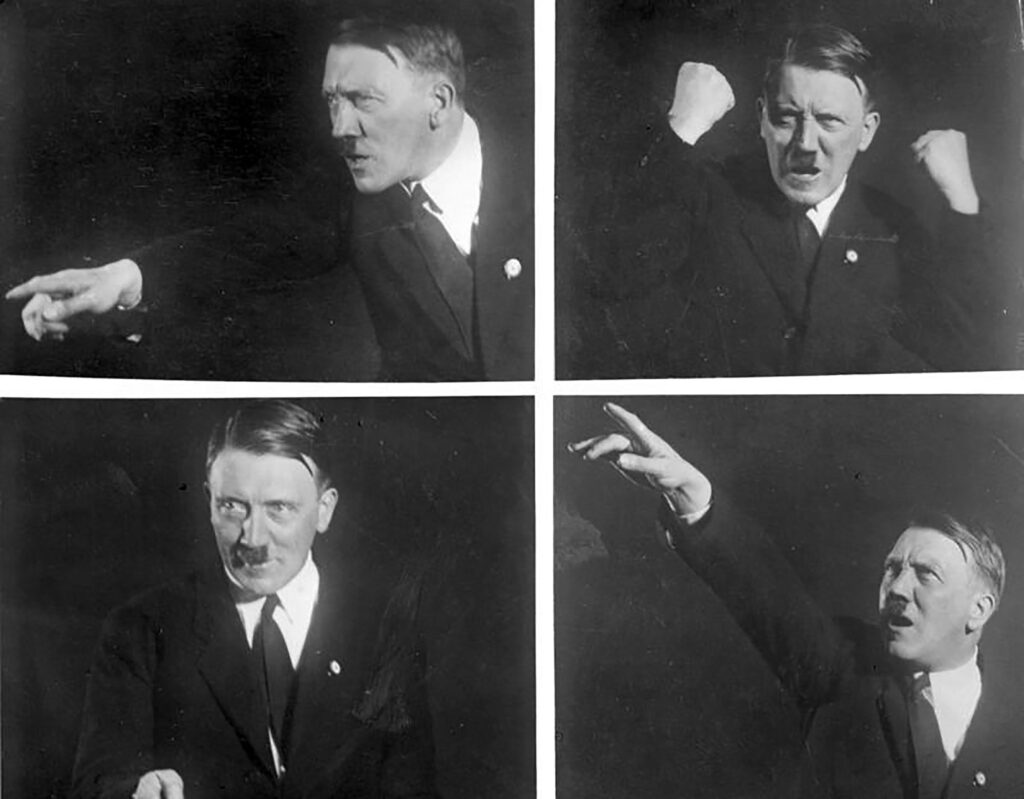

Heinrich Hoffmann / German Federal Archives via Wikimedia

“In Italy in the early 1920s,” Connelly said, “there was a sense across the political spectrum: We need a person who can really break through these old, decrepit structures of liberal order that went back several decades to the creation of modern Italy.

“Mussolini appealed to people of many backgrounds, in the center of the political spectrum, as a force of order and strength. As a former socialist, he could project concern for the broad populace.”

Similar social dynamics allowed Hitler to rise to power. Both he and Mussolini emerged from the humiliation and bitterness of World War I on a promise to restore the greatness of the nation and its people.

It’s an essential point: None of the Berkeley scholars put Trump in the same category as Hitler or Mussolini. But, they said, it’s difficult to ignore some similarities between them.

Each of them has been described as chronically dishonest and highly manipulative. Each had a flamboyant, theatrical speaking style, and they were able to summon the admiration and provoke the fury of their fanatically loyal supporters. Both Hitler and Mussolini served time in jail, while Trump has been found liable for a range of criminal and civil offenses and could be facing jail time. Their legions held steady.

We’re gonna put kids in cages. It’s going to be glorious.”

Mike Davis, a top legal adviser to former President Donald Trump

Trump has never sought overtly to become a dictator, but he has at times suggested that he might. He consistently held himself out as a man of singular strength who could rescue the nation when other leaders and institutions failed.

“I alone can fix it,” he famously said in his first campaign. Later, he proclaimed to his followers: “I am your warrior. I am your justice. And for those who have been wronged and betrayed: I am your retribution.”

All three men were at times seen as messiahs. And all survived assassination attempts.

Condition No. 4: The leader employs violence to impose order and obedience

Fascism, said Rosenthal, historically is characterized by the use of organized militias that answer to the leader or the state, deployed to impose order and consolidate fascist power — often through violence.

Mussolini sent his Blackshirts to the March on Rome in 1922 to threaten the national government, and the government capitulated. Stormtroopers attached to the Nazi Party violently harassed communists, Jews and others and were a critical force in Hitler’s rise to power.

Wikipedi

While Trump never had a MAGA militia, he has encouraged followers to assault protesters or journalists. Through his first term, he built a loose alliance with the Proud Boys, the Oath Keepers and other armed groups that embrace hard-right, often racist ideology.

Trump in effect summoned them to Washington, D.C., on the eve of congressional certification of Democrat Joe Biden’s win in the November 2020 election, and then seemed to incite them just before the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Leaders and members of those militia groups have been prosecuted and imprisoned for their violent effort to prevent an orderly transfer of power. Trump has described them as political prisoners, and has said he “absolutely” would consider pardoning them if he’s re-elected.

Condition No. 5: The leader identifies scapegoats and attacks them relentlessly

Right-wing populism, said Connelly, “is always directed against others. What unites all of these forces is a hostility to foreigners, to people who are different, to the other. Hitler was overtly anti-Semitic, an overt racist. Mussolini was anti-Slavic because of the perception that Croatians and Slovenians had stolen Italian territory.”

Hitler’s rhetoric had a sharp, sinister edge. Said Solovy: “There’s no doubt that it enabled violence and genocide.”

Trump’s use of scapegoating has been a defining trait of his movement. In the initial days of his presidency, he banned people from six Muslim-majority countries from entering the U.S. His movement has featured escalating attacks on LGBTQ+ and transgender people. He has persistently insulted and condemned migrants crossing the southern border into the U.S., calling them at various times rapists, mentally ill and “vermin” who are, in his view, “poisoning the blood of our country.”

Critics have noted the similarity of Trump’s dehumanizing language to Nazi smears against the Jews.

Still, fierce opposition to immigration remains central to the MAGA movement, and it is a crucial focus of the controversial Project 2025 plan that is seen as a blueprint for a second Trump term. Trump’s allies have openly predicted that, if he’s reelected, the government will round up millions of legal and undocumented migrants, hold them in mass concentration camps, and then deport them.

Attorney Mike Davis, a former Supreme Court clerk whose name has been floated as a possible U.S. attorney general under Trump, recently described these goals in chilling detail:

“We’re gonna deport a lot of people, 10 million people and growing — anchor babies, their parents, their grandparents. We’re gonna put kids in cages. It’s going to be glorious.”

Condition No. 6: Democratic institutions remove limits on the leader’s authority

There is a final parallel — and for some of the scholars, one of jarring importance.

Early in the leadership of both Mussolini and Hitler, lawmaking bodies gave them enormous authority to suspend rights and processes in place under Italian and German democracy.

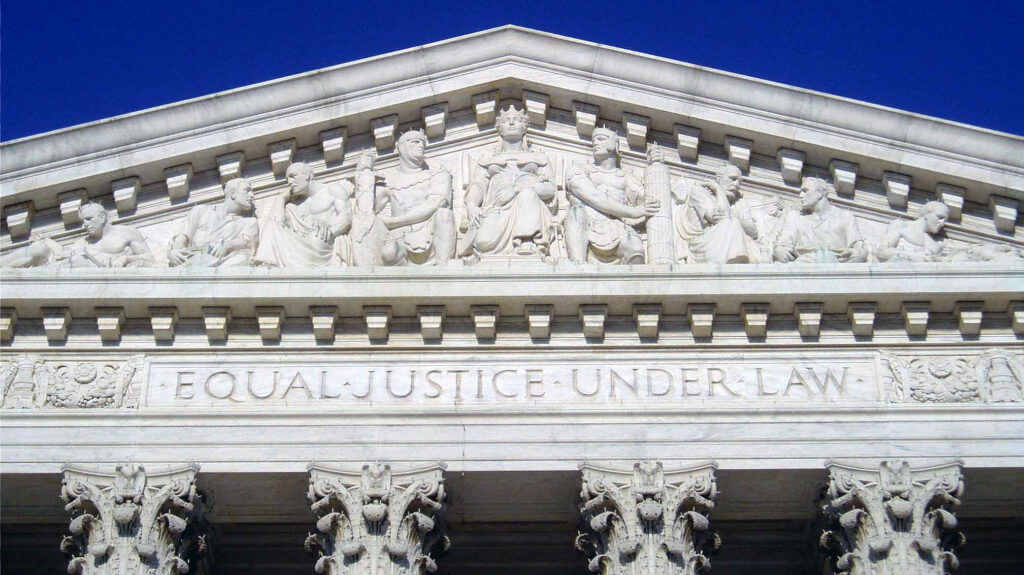

The U.S. Supreme Court, just two months ago, issued a controversial landmark ruling that seems to give presidents broad immunity from prosecution if they break laws in the course of their duties.

MattWade via Wikimedia Commons

How does that decision compare to the rulings in Europe during the rise of fascism?

“This is probably the most controversial thing I can say,” Rosenthal replied, “but I believe that there is a parallel between the German Enabling Act in 1933 and the Supreme Court decision on immunity.”

The U.S. court ruled that “the president essentially enjoys impunity,” Connelly added. “They’re withdrawing themselves from the process, when they’re supposed to be a check on the process. Similarly, institutional checks on abuse of power failed in Germany.”

The U.S. has its own unique strains of illiberalism

For Large and Wittenberg, the idea that conditions in the U.S. match those in post-WWI Italy and Germany goes only so far. For both, the parallels diverge in important ways.

Even before the U.S. formed in the late 1700s, Large said, an anti-democratic impulse was evident. That was most acute in matters of race and ethnicity: slavery and the Civil War, genocide against Indigenous people; Supreme Court rulings that justified segregation Jim Crow laws and lynchings. Wave after wave of immigrants arrived in the U.S. to a fiercely hostile reception.

Underwood & Underwood, from the U.S. Library of Congress

In Europe a century ago, there was no force comparable to the hard-right evangelical Christians who form a core of the MAGA movement. Nor did Europe allow almost unchecked private possession of guns. Today in the U.S., thousands — perhaps millions — in the MAGA ranks own weapons of war. Many of them consider guns a right ordained by God.

Those currents in American culture today resist any control on guns, despite epidemic mass shootings. MAGA forces seek to ban the teaching of the nation’s racial history in schools, and they justify sweeping campaigns to control women’s reproductive rights and to strip basic rights from LGBTQ+ Americans.

“I don’t think we have to say, ‘Oh God, we’re in trouble in this country because we’re going to go fascist like the Europeans,’” Large said. “I say we’re in trouble because we’re going to go fascist like the Americans.”

Photo from Masters for Senate campaign video.

Wittenberg, the political scientist, acknowledges such worries. But in his view, there is no practical way that Trump or any other president could impose an authoritarian government. The country is too big, he said. Our institutions are too dispersed, too entrenched. The military would never go along.

A greater concern, for Wittenberg, is that by exaggerating the risk of an authoritarian takeover, we’ll miss the slow erosion of democratic institutions and processes driven by both Republicans and Democrats — the greater use of executive orders by presidents, for example, or simply our uncompromising resistance to outcomes in which our opponents win.

Suppose Trump is reelected, he mused, and suppose his administration weakens or abolishes the Environmental Protection Agency.

“So we’ll have dirtier air,” he said. Some voters will be furious, “but there’s nothing essential to democracy about having clean air. The Constitution explicitly states that powers not mentioned in that document are thrown back to the states. So arguably, it’s more democratic.”

Congress can block the effort or impeach the president, or voters can challenge the decision in court. It’s messy, Wittenberg said, but that’s the nature of our system.

“Democracy doesn’t always give you good outcomes,” he said. “You know, democracy produces people like Trump. And if you think that people like Trump should not be allowed to run for president, or support efforts to invalidate his candidacy, then you have a problem with democracy.”

The guardrails of democracy may not be as strong as we think

With Kamala Harris surging in the polls and the Trump campaign struggling to gain traction, there’s a temptation to believe that the risk of a democratic crack-up might soon be erased. But several scholars cautioned against that view. The anti-democratic dynamics that shape our era will not go away with one election, they say.

And so the future seems to turn on a central question: Is Wittenberg right, that what happened in Germany and Italy can’t happen here? Or could a majority of Americans turn against democracy, as Italians and Germans did a century ago?

Both Rosenthal and Large agree that the nation’s long tradition of democracy and its deeply embedded institutions are far stronger than those in Italy and Germany.

“That’s true, and that can help,” Large said. “But I don’t think the guardrails are as strong as a lot of people think.”

Compared to Germany and Italy, “the mountain to climb in America is much steeper for illiberal movements,” Rosenthal added. “I agree with that 100%. But there is a cliché which says that when these things go, they go quickly. I would add that as an addendum.”

Which leaves Americans and the rest of the world to closely watch the guardrails leading up to Nov. 5, and in the weeks after. The future is uncertain — and that, too, is how democracy works.

“In the next several months, there are going to be surprises,” Rosenthal said. “That’s the only thing we can be certain of.”

Related

A New Book Argues That What Happens in Europe Doesn’t…

Remaking the World: European Distinctiveness and the Transformation of Politics, Culture, and the Economy by Jerrold Seigel “No issue in world

Poland plans military training for every adult male amid growing…

Poland’s prime minister, Donald Tusk, has said his government is working on a plan to prepare large-scale military training for every adult male in response t

2025 European Athletics Indoor Championships: Ditaji Kambundji secures women’s 60m…

Switzerland’s Ditaji Kambundji walked away from the 2025 European Athletics Indoor Championships in Apeldoorn on 7 March with much more than her first Europea

Takeaways from the EU’s landmark security summit after Trump said…

BRUSSELS (AP) — European Union leaders are trumpeting their endorsement of a plan to free up hundreds of billions of