European elections 2024: 11 important things to watch for

When Europeans vote in elections for the European Parliament this coming week, their choices will reflect the national mood in 27 different countries.

Right and far-right parties are set to make gains, but the picture is widely different across the continent. Here is a snapshot of what to expect from BBC correspondents ahead of the vote.

Young leader boosts French far-right appeal

Marianne Baisnée/BBC

Marianne Baisnée/BBCHugh Schofield in Paris

The main point of suspense in France is how big will be the victory of the far right under its 28-year-old leader Jordan Bardella.

President Macron is certain to take a thumping. The question is whether his Renaissance party can limit the damage by at least retaining second place.

It is far from a given, with the Socialists under a strongly performing Raphaël Glucksmann snapping at the heels of Macron’s little-known champion Valérie Hayer. In the polls, they are each at about 15% or thereabouts, while other parties are hovering a little above the 5% cut-off, below which they will return no MEPs at all.

Meanwhile, Jordan Bardella and National Rally are consistently polling at 32% plus – more than double their nearest rivals.

The far right also won the last European elections in France in 2019, but by only a tiny lead over President Macron’s party.

This time it looks like being a crushing victory. Clearly many voters who want to give a kicking to the president think that the most effective way is to choose the far right. Any inhibitions that might have checked that vote in the past have all but vanished.

Will Belgium still be a country?

HATIM KAGHAT/BELGA/AFP

HATIM KAGHAT/BELGA/AFPBruno Boelpaep in Brussels

Most Belgians have no idea whether the election posters are after their vote at a European, federal or regional level. Because on 9 June, Belgians are electing MPs for seven different parliaments.

Only one vote has got the country talking. And it’s not the European election but the federal vote, because the future of Belgium might well be at stake in Flanders, the Flemish north.

To be able to govern and choose a prime minister, Flemish and French-speaking parties will have to form a coalition at the federal level.

However, all the polls indicate that far-right party Vlaams Belang will come first. It wants the independence of Flanders and therefore the end of Belgium.

Until now, the traditional parties have kept a pact to keep it out of the ruling coalition. But as the prospect rises of Vlaams Belang coming first, so does the pressure on the other parties to let them have a seat at the table.

Poles vote with Russia’s war on their minds

SERGEI GAPON/AFP

SERGEI GAPON/AFP Adam Easton in Warsaw

Polling suggests Russia’s invasion of neighbouring Ukraine is the issue over the last decade that has most changed the way Poles see the future.

That may explain why Poland’s centrist, pro-EU prime minister Donald Tusk has made national security and Russia’s threat the number one issue in his election campaign.

He’s trying to break a run that’s seen the Eurosceptic Law and Justice (PiS) party win the last nine elections, including October’s parliamentary and April’s local elections, although PiS’s lack of coalition partners saw it lose power in both.

Turnout is usually low, so both parties are keen to get their core voters out.

For PiS, that means playing on fears of abandoning the Polish zloty for the euro, rising energy prices and the impact of the EU’s climate policies on farmers.

Opinion polls put Donald Tusk’s Civic Coalition and PiS way out in front, tied on around 30% each.

Muted Slovak campaign after PM Fico’s shooting

Reuters

ReutersRob Cameron in Prague

Slovaks vote next Saturday amid a strange, muted and at times tense atmosphere that has descended on their country since the assassination attempt on Prime Minister Robert Fico.

The centre-right opposition immediately suspended campaigning after the 15 May shooting, when Mr Fico went to greet supporters in the town of Handlova. He has only recently left hospital.

His left-populist Smer party is now leading the opinion polls following the shooting, which authorities say was politically motivated.

Smer opposes sending weapons to Ukraine and instead styles itself as the “peace” party.

It has eclipsed the centre-right opposition Progressive Slovakia, whose leader Michal Simecka was previously a deputy chairman of the European Parliament.

Last year’s election campaign was marred by insults, threats and even a punch-up between ex-prime minister Igor Matovic and Mr Fico’s deputy Robert Kalinak, who is now de facto acting prime minister.

Politicians on all sides are now under pressure to keep the temperature lower.

Austrians pulled by far-right promises

JOE KLAMAR/AFP

JOE KLAMAR/AFPBethany Bell in Vienna

“Stop EU Chaos, Asylum Crisis, Climate Terror, War-mongering, Corona Chaos,” declares one poster for the far-right opposition Freedom Party (FPÖ), who lead the polls here.

Another image shows the head of the European Commission embracing the Ukrainian president. The governing conservative People’s Party (ÖVP) has condemned the image as Russian propaganda.

Political analyst Thomas Hofer says in the past the Eurosceptic FPÖ has had trouble mobilising its supporters for EU elections. But now 27% of Austrians say they will vote for the party, ahead of the People’s Party and the opposition Social Democrats, who are each polling at 22%.

The Green Party is struggling, after questions arose about its lead candidate, Lena Schilling, a 23-year-old climate activist. She was accused of spreading damaging rumours and being disloyal to the Greens, which she denies.

With Austria’s general election this autumn, this vote is being watched very carefully.

Big chance for Italy’s Giorgia Meloni

MASSIMO PERCOSSI/EPA-EFE

MASSIMO PERCOSSI/EPA-EFEBy Laura Gozzi

At the last European elections, Matteo Salvini’s League came out top with over 34% of the vote. Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy (FdI) hovered around 6%.

The situation is now about to be reversed. FdI is set to win 27% of the vote – largely at the expense of the League, which will tumble down to just over 8%.

It is a remarkable result for Ms Meloni, who in the space of five years has gone from being a noisy but relatively minor opposition figure to prime minister and leader of Italy’s ruling coalition – in which the League is a junior partner.

While Mr Salvini seems condemned to espousing increasingly radical positions in an attempt to stop haemorrhaging voters, Ms Meloni finds herself in the enviable position of being courted by French National Rally leader Marine Le Pen and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, both of whom want her support on the European stage.

Ms Meloni has already reshaped Italy. She might now get the chance to do the same to the EU.

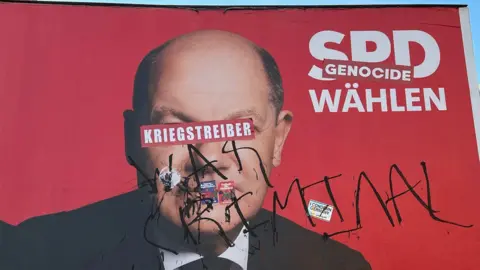

Germany’s Scholz set to take hit over war

Ali Zaidi/BBC

Ali Zaidi/BBCDamien McGuinness in Berlin

Frieden, or peace, is the word most often cropping up on campaign posters here. For radical, left-wing parties that means a halt to arming Ukraine.

But for Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who is presenting himself as “peace chancellor”, it’s about calming voters’ fears of escalation.

His government is the largest donor of military aid to Ukraine in Europe, but he has repeatedly set red lines on some weapons, tapping into his centre-left SPD party’s anti-war heritage.

“Warmonger” is the graffiti scrawled on his face on some posters. “Ditherer” is the accusation from some critics in parliament and the media.

The danger is that he may simply alienate both sides. His party, like all three governing coalition parties, is set to get fewer votes than last time.

The conservative opposition leads the polls, and the big question is whether the far-right AfD, despite a string of recent scandals, will beat Mr Scholz’s SPD into second place.

Hungary’s Orban faces strong challenge

Nick Thorpe/BBC

Nick Thorpe/BBCNick Thorpe in Budapest

Hungarian leader Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party hoped to romp home with an easy victory, then help reshuffle Europe’s right wing.

Pushed out of the EU’s centre-right European Peoples Party, Fidesz wants a new group with Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and France’s Marine Le Pen that would be “a force for Europe”.

Mr Orban’s plans have been dented but not destroyed by the emergence of former Fidesz insider Peter Magyar and his new TISZA party.

Peter Magyar has been touring the country, drawing large crowds and striking a deep chord with tirades against Fidesz corruption, the disastrous state of schools and hospitals, constant emigration, and growing numbers of migrant workers from Asia.

His aim is to squeeze the Fidesz vote now then defeat Mr Orban in the next national election in 2026. Fidesz is on 44% and falling; TISZA is on 26% and still rising.

The Hungarian PM says EU leaders and the US are warmongers over Ukraine – and 9 June is a simple vote between peace and war.

Spain’s conservatives pile pressure on PM Sánchez

by Javier Lizon/EPA-EFE

by Javier Lizon/EPA-EFEGuy Hedgecoe in Madrid

The conservative People’s Party (PP) looks likely to make the most gains, as it takes votes from the struggling Ciudadanos, which could lose all eight of its seats.

For PP leader Alberto Núñez Feijóo, this is an opportunity to pile the pressure on Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, whose government he is seeking to portray as corrupt – because of a judicial investigation into his wife, Begoña Gómez – and in hock to Catalan nationalists.

Mr Sánchez hopes recent foreign policy set-pieces, such as the announcement of a large military package for Ukraine and his government’s recognition of a Palestinian state, will help ensure a reasonable result.

The far-right Vox tends to thrive on turmoil surrounding Spain’s territorial issue and with the government’s controversial amnesty for Catalan nationalists hogging the headlines recently, polls suggest it is going to make gains.

A new far-right party, Se Acabó la Fiesta (The Party’s Over) led by online agitator Alvise Pérez, could secure a seat.

Polarised Dutch still reeling after last election

KOEN VAN WEEL/EPA

KOEN VAN WEEL/EPAAnna Holligan in The Hague

Billboards along canals and bike lanes display a patchwork of candidates. A record 20 parties are taking part, but many here are tired of politics and turnout is likely to be low.

The Netherlands is still reeling from the twists and turns in forming a new government after November’s parliamentary elections.

The issues of that vote haven’t gone away: immigration, a nationwide housing shortage, climate change and the future of farming.

Geert Wilders’ far-right Freedom Party (PVV) won the 2023 election and has dropped a longstanding pledge to hold a “Nexit” vote, recognising there is limited appetite for a Dutch Brexit.

The polls suggest his party and the other three that are set to form the next Dutch government – the liberal conservative VVD, the centrist New Social Contact and the Farmer Citizen Movement (BBB)) – will almost half the 31 Dutch seats in the European Parliament.

In a politically polarised society, it’s the Eurosceptic right and pro-EU left that are poised to make the greatest gains.

Denmark’s vote a test for flagging government

Reuters

ReutersAdrienne Murray in Copenhagen

Across Denmark’s capital Copenhagen, posters of candidates are tied to lampposts and trees on just about every street in the city, as almost 170 them from 11 different parties, compete for 15 seats in the European Parliament.

This election may well end up being a litmus test for Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen and her centrist coalition government, which straddles the traditional left-right divide.

Her Social Democrats have fallen back in the polls since the 2022 general election, and her coalition partners, the Liberals and the Moderates, are also trailing.

But while Mette Frederiksen talks tough on migration policy and urges Europe’s left to tighten their stance, it’s the climate crisis that ranks among the most important issues for voters here.

Farming is the new battleground that runs along Denmark’s urban-rural divide. There is heated debate over agriculture’s emissions footprint and a proposed carbon tax.

Defence is also a big issue, as are terror, crime and the future of Europe.

Related

European leaders push defense spend amid uncertainty over Trump aid…

This week, the European Commission proposed measures for fiscal flexibility on defense spending and a plan to borrow 150 billion euros ($163 b

Europe rallies behind Zelensky as US announces new talks with…

EU leaders rallied around Ukraine and agreed to boost the bloc's defences at a crisis summit Thursday, as Washington said talks with Kyiv were back on track

European markets recoup most losses; Autos gain on tariff exemption

This was CNBC's live blog covering European markets. European markets ended around the flatline on Thursday after a choppy day of trading as i

Jesse Eisenberg Granted Polish Citizenship: ‘I Am Happy to Be…

Jesse Eisenberg has been granted Polish citizenship by the European country’s president, just months after the actor, writer and director applied.Eisenberg wa